Interactive functions and reports of anxiety

We report here on research we undertook to examine the entrance tests for applicants to second-language teaching programs in either English or French. In particular, we were interested in examining the speaking portion of this test, a one-on-one telephone interview. Individual one-on-one interviews are still the most common method of assessing speaking for high stakes contexts such as these (Luoma, 2004), and they are often conducted by telephone for cost and time savings.

This oral interview task follows a standard format, consisting of a warm-up, two separate tasks (a role play with the interviewer and a single long turn discussing an opinion on an issue), and a wind-down. The complete interview lasts approximately 10 to 15 minutes. As with many current speaking tests (see Luoma, 2004), this oral interview was designed to capture information not just on language accuracy but on the ability to engage in a variety of interactional language functions, like being able to interrupt appropriately and politely, introduce topics, and manage turn-taking. However, sometimes oral tests do not succeed in doing this, instead being much less interactive: simply a series of answers to interviewer questions. So, we were interested in examining whether a variety of language functions were actually being elicited. If they were, then the test is more useful in making decisions about these future teachers’ interactive abilities in the language that they hope to be teaching.

In addition, we were also interested in how the telephone format affected the level of anxiety of the test candidates. Language test anxiety is a well-known phenomenon (see Horwitz; 1996; Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986) and anxiety has been shown to affect both the quantity and quality of linguistic output (e.g., Toth, 2012). There is some evidence that test candidates may have a preference for a face-to-face format, as it is more like authentic interaction (Qian, 2009), but there is little work on test-taker reports of anxiety with this particular test delivery method.

Therefore, our research questions were the following:

- What is the nature of the interactive functions elicited by the telephone tasks?

- How has the telephone format of the test affected feelings of anxiety in the test candidates (the applicants to the teacher training program)?

Method

In our study, we were informed by Weir’s sociocultural model for test validation (Weir, 2005; see Taylor, 2011, for a slightly adapted version of the framework for the conceptualisation of speaking validity specifically). This framework allows for the collection of evidence to support the claims made for the use of this particular test.

Recorded Telephone Interviews

Audio recordings of the admissions telephone interview were obtained from the language testing administrators following university ethical approvals. The full interview database consisted of three versions of both the role-play and the opinion tasks. While further details cannot be provided for reasons of test security, the role play that was selected was a mock job interview, and the opinion task selected was the candidates’ position on an educational topic.

A sample of 32 recordings was then chosen for qualitative analysis: 16 each for the role- play and the opinion tasks. Four recordings were chosen of English speakers being tested in English (their native language), four of French speakers being tested in English, four of French speakers being tested in French, and four of English speakers being tested in French. To control for the language proficiency of test takers in our analysis, the 16 task recordings that were chosen from among those receiving a grade of 4/5 (a clear pass) on the rating scale developed for the assessment. It was decided that recordings receiving a clear pass would be most suitable as the object of analysis because a variety of interactional functions is more likely to be elicited by successful candidates.

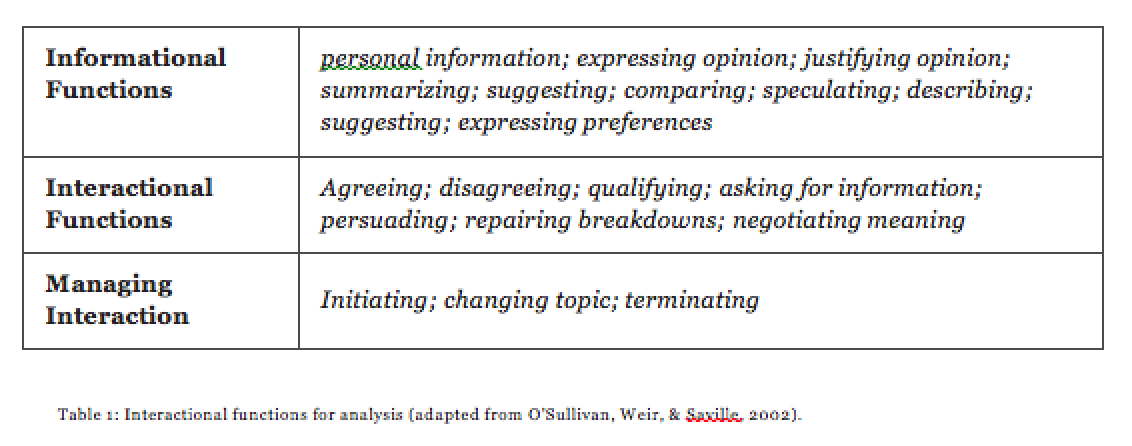

After the final 32 recordings were selected, each was analysed with an adapted version of the observational checklist used to validate speaking assessment tasks developed by O’Sullivan, Weir, and Saville (2002). Since that time, a variety of forms of this observation checklist have been used in test validation applications, including investigations of test form comparability (Weir & Wu, 2006) and for the collection of a priori validity evidence in speaking test development (Nakatsuhara, 2014).

This practical checklist was developed specifically for use while listening to oral responses, without the need for transcription. The checklist was adapted for our purposes in a three- step process. First, one researcher initially listened to all recordings and noted which functions were used or could conceivably be applied. This formed the initial list. Secondly, the test specifications documents were consulted and all interactive functions that were cited as the focus of the tasks in this document were included. This required adding some functions to the original list (such as changing topic), but it was important to look specifically for the functions referenced in the test development documents. Finally, all researchers engaged in a group piloting session with the tool, listening to full interviews, to determine whether all utterances in the interviews could be assigned a function. In this manner, we were able to combine some categories and come up with as parsimonious a list as possible for practical and efficient use. The functions included in this adapted checklist can be found in Table 1 below.

Questionnaire

To respond to our second research question we made use of an adapted version of the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS; Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986). The FLCAS uses a Likert scale to assess the agreement participants report on statements regarding their anxiety related to interacting in a foreign language instructional setting. This scale has proven to be valid for making useful inferences of anxiety in language students. The team examined all items and chose those which related to language assessment. We then translated the questionnaire from English to French in order to allow participants to complete the questionnaire in their choice of language.

The first three questions requested details regarding participants’ language preferences. This allowed us to gain insight into perceived comfort levels while speaking English or French, or both. Participants were left space where they could explain in more detail which language they felt more comfortable speaking. For the purposes of this study, we did not include demographic information about other languages, only reported comfort in the languages of the test—English or French.

Questions four and five were designed to activate the participants’ memories of the test event. Participants were asked to think back to when they completed the test, the topics they discussed, and the friendliness of the interviewer. The participants then responded to the anxiety-related items, and opinions about how the telephone test delivery format affected these anxiety levels. As a final open-ended question, we asked participants to provide us with any other information that they felt they would like to share with us regarding their telephone interview experience. The full questionnaire is included in Appendix A.

In April, 2015, upon permission from the instructors, we visited two first-year language teaching methodology classes, one in French and one in English, explained the purpose of our study, and requested that students complete the questionnaire. Thirty-one students voluntarily completed the questionnaire in the two classes.

Results and Discussion

We found that the two tasks (the role play and an opinion long turn) differed in the interactional functions they elicited. As might be expected, informational functions dominated the opinion task. The opinion task was worded in such a way that candidates were able to engage in comparing (20 instances), expressing opinion (83 instances), justifying opinion (61 instances), and speculating (44 instances). These functions were either very rare or non-existent in the role-play task (where, for example, justifying opinion occurred only 6 times). On the other hand, only the role-play task elicited interaction management functions such as initiating and terminating interactions. Overall, the role-play task elicited a greater variety of functions, with at least a few instances of informational, interactional, and managing interaction functions. Therefore, the use of two tasks in the assessment is beneficial as it increases the coverage of language functions produced by the applicants.

An important finding also is the number of interactive functions that are NOT performed: many functions are elicited rarely or not at all by either of the tasks, including agreeing and disagreeing, changing topic, and suggesting. If we judge the quality of the task by the variety of interactive functions in which the candidate is able to engage, then there is improvement to be made. The interviewer might be able to encourage more use of the above interactive functions by mentioning them explicitly (e.g., “persuade me;” “what parts do you agree and disagree with?”).

There is a challenge in eliciting a variety of functions due to the unequal power relationship between the test taker and interviewer: the interaction is managed primarily by the interviewer. This power differential, sometimes called interviewer dominance, has been well established for decades (see Lazaraton, 1992; Young & Milanovic, 1992). However, Kormos (1999) suggests that while non-scripted interviews are characterised by dominance of the interviewer, these roles can be reversed in role-play tasks where there can be interaction that is more “symmetrical”. So there is potential for the role-play task to be designed to overcome challenges in the power differential as well as the variety of functions elicited. For example, it would be very interesting to explore the use of a role-play task where the test taker has the role with the higher position of relative power. If the test taker were the person conducting a job interview, for example, then more of the responsibility for interaction management would fall on his or her shoulders. This loss of control for the interviewer means greater authenticity as well as more even interaction, but represents other challenges for both reliability and validity. How, for example, can similar test lengths for all candidates be ensured, if the candidates decide when to wrap up the interaction? The challenge is in creating tasks that allow for the power sharing that is indicative of the target domain, while providing reasonably equivalent testing conditions for all candidates.

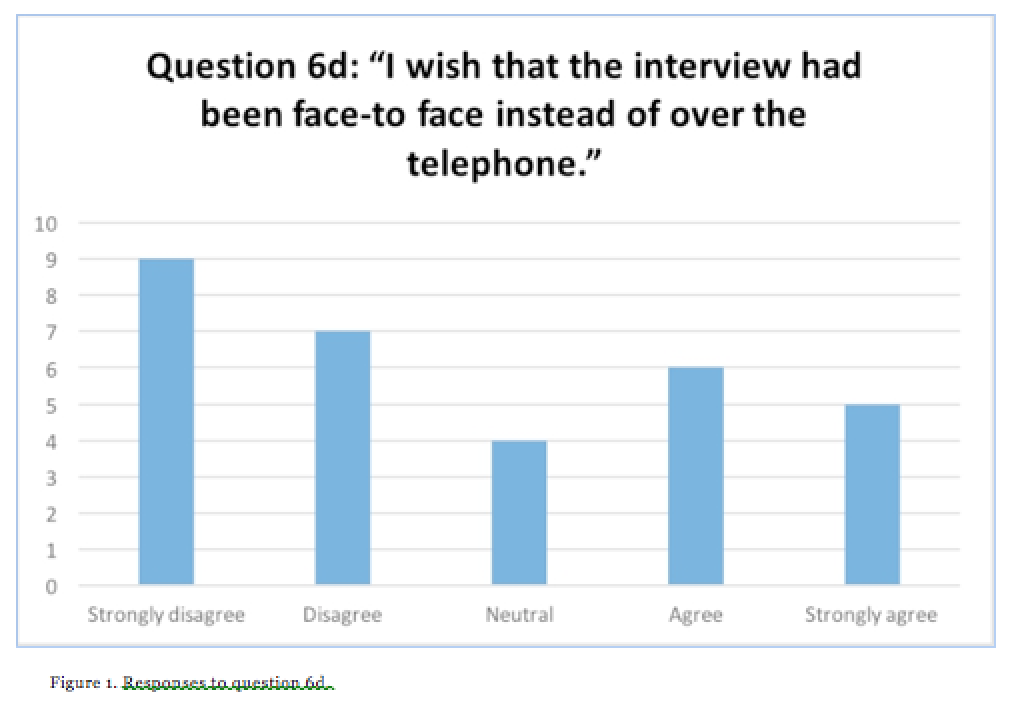

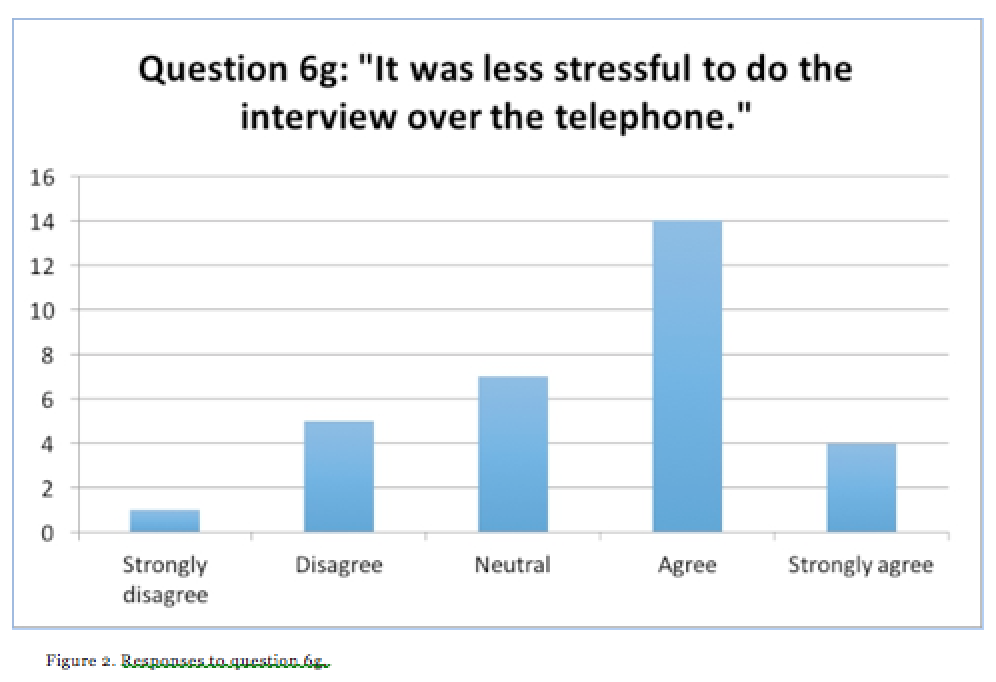

Regarding our second research question related to anxiety, we found that the telephone format did not appear to have created more anxiety amongst test takers. The average response to Statement 6d, “I wish that the interview had been face-to face instead of over the telephone,” was 2.5 (SD 1.4). Note that 5 equals strong agreement, 3 is neutral, and 1 equals strong disagreement with the statement, so while there is some divided opinion there is a slight preference to the telephone interview over the face-to-face form. In addition, most respondents were in agreement with Statement 6g, “It was less stressful to do the interview over the phone,” for both tests and all the groups of respondents (M=3.48; SD 1.02). There was no significant difference between English and French test takers on either of these questions. Figures 1 and 2, below, summarise the individual responses to this question.

There was mild anxiety reported that did not have to do with the telephone format. The mean response for all anxiety-related questions is 2.6 (SD=1.25). This sentiment can be illustrated with the following comment by one student: “Au début, cela était un peu plus difficile avec le stress de parler, mais à fur et à[sic] mesure que l’entretien avançait, mieux c’était. La personne m’a aider [sic] à diminuer le stress un peu.” (At first, it was a little more difficult with the stress of having to talk, but as the interview went along, the better it got. The [interviewer] helped to reduce the stress a little.)

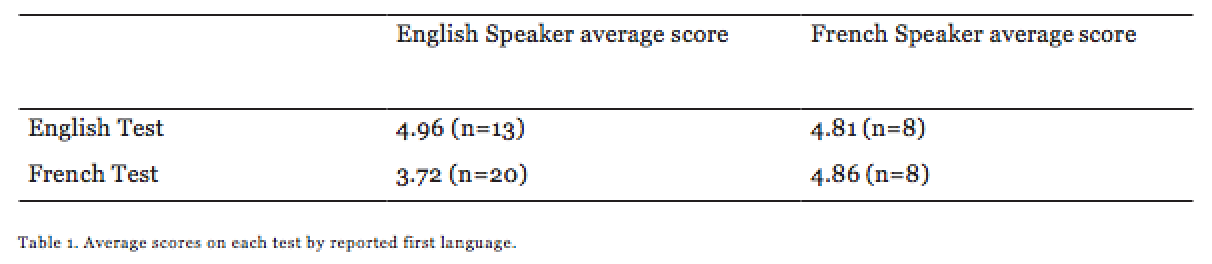

In addition, English native speaker respondents taking the French test reported significantly greater anxiety than French native speakers taking the English test (M= 2.91;SD=1.2; p=.007). One explanation for this finding is that there were some difficulties with the delivery of the French test: several respondents who were tested in French indicated difficulty with finding the right phone number, whereas there were no issues reported with conducting the English version of the test. We might therefore question if both versions of the test would initially cause the same (relatively low) level of anxiety among test takers in both languages, but these additional logistic obstacles could have increased stress levels.

Another explanation is related to language proficiency. English applicants to the French teaching program have a lower relative proficiency level (see Table 1 below):

In fact, almost all the students who failed this particular exam and who were not admitted were English native speakers doing the French exam Literature has demonstrated that greater anxiety is associated with the lower proficiency levels (e.g., Liu, 2007; Tsai, 2013; Zhang & Liu, 2013). One English respondent made the suggestion that more information about the test content and format ahead of time would be helpful in reducing stress, as illustrated by the comment by E13: “If examples of what we would be interviewed on were provided prior, it would be less stressful. As I didn’t know I would be doing a pretend skit I was worried wondering what it is I would be asked.”

Conclusions and Future Work

We addressed the nature of interactive functions elicited by the telephone tasks and found that the role play task elicited a greater variety of such functions compared to the opinion task. Some functions were notably absent, and those related to interaction management were still limited. These functions can only be more present if the test candidates were given more control of the interaction. The fact that the role play enabled more opportunity for interaction management was sensed very clearly by student E5, who mentioned “I think doing a role play made it easier to take the lead and answer. However, that does not make it any less stressful!” This anxiety, in general, was not found to be extreme. In general, the participants did not show any particular concern about the telephone format of the test. Based on these results, we made the following recommendations to the test developers:

- In designing the written script for interviewers, it may be possible to increase the variety of certain interactional functions by naming them explicitly (e.g., with persuade, summarise, and agree/disagree).

- Test designers may want to design a role play task where the candidate is given a “character” to play who has relatively higher power in the interaction, in order to investigate the effects of this change on the nature of interactive functions produced.

- It does not seem problematic at this time to continue with telephone formats for interviews, in terms of anxiety. While stress levels are not exaggerated, this stress may be mitigated even further if additional information was provided to test takers about the test format and content, to the extent possible. This is in keeping with best practice in the field of language assessment (ILTA, 2007).

This validation study was small in scope, but was still found to result in useful evidence for increasing the quality of the test that is offered. This is a high-stakes test, playing a role in the selection of future members of the language teaching profession in Ontario and elsewhere. Efforts must be taken to develop tasks that allow university decision makers to draw meaningful inferences about these applicants’ interactive abilities. Therefore, speaking-assessment tasks need to shake the interviewees out of their passive roles, where they can demonstrate their rhetorical skills and their abilities to initiate and manage interaction.

References

Horwitz, E. (1996). Preliminary Evidence for the Reliability and Validity of a Foreign Language Anxiety Scale. TESOL Quarterly, 20(3), 559–562.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 125–132.

ILTA (International Language Testing Association; 2007). Guidelines for Practice. Retrieved from: http://iltaonline.com/images/pdfs/ilta_guidelines.pdf

Kormos, J. (1999). Simulating conversations in oral proficiency assessment: A conversation analysis of role plays and non-scripted interviews in language exams. Language Testing, 16(2), 163–188.

Lazaraton, A. (1992). The structural organization of a language interview: A conversation analytic perspective. System, 20, 373–386.

Liu, M. (2007). Anxiety in oral English testing situations. ITL: International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 153, 53–76.

Luoma, S. (2004). Assessing Speaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Sullivan, B., Weir, C., & Saville, N. (2002). Using observation checklists to validate speaking-test tasks. Language Testing, 19(1), 33–56.

Qian, D. D. (2009). Comparing direct and semi-direct modes for speaking assessment: Affective effects on test takers. Language Assessment Quarterly, 6(2), 113–125.

Sturges, J. E. & Hanrahan, K.J. (2004). Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qualitative Research, 2(1), 107–118.

Taylor (2011). In Taylor, L. (Ed.), Examining Speaking: Research and practice in assessing second language speaking. Studies in Language Testing 30. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Toth, Z. (2012). Foreign language anxiety and oral performance: Differences between high- vs. low- anxious EFL students. US-China Foreign Language, 10(5), 1166–1178.

Tsai, C. (2013). The impact of foreign language anxiety, test anxiety, and self-efficacy among senior high school students in Taiwan. International Journal of English Language and Linguistics Research, 1(3), 1–17.

Weir, C. (2005). Language testing and validation: An evidence-based approach. Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstoke.

Young, R., & Milanovic, M. (1992). Discourse variation in oral proficiency interviews. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 14, 403–424.

Zhang, W. & Liu, M. (2013). Evaluating the impact of oral test anxiety and speaking strategy use on oral English performance. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 10(2), 115–148.

Author Bios

Beverly Baker is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Language Assessment Sector at the Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute at the University of Ottawa.

Joselyn Brooksbank is an MA student in Bilingualism Studies at the University of Ottawa, with an interest in family language policy, early childhood bilingualism, and Montessori education.

Irina Goundareva recently completed her PhD in Spanish Linguistics from the University of Ottawa, specialized in foreign language acquisition and Spanish language teaching.

Valerie Kolesova is an ESL instructor and an MA student in Bilingualism Studies at the University of Ottawa, focusing on acquisition and assessment of sociopragmatic competence.

Jessica McGregor is an MA student in Bilingualism Studies at the University of Ottawa, focusing on the secondary course selection process in French as a second language, with a secondary interest in language identity and ideologies.

Mélissa Pésant completed her MA in Bilingualism Studies in 2015. Her major research paper was on the resources used in second language textual revision. She is currently working in England as a French second language teacher.