Abstract

The article introduces the application of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model (1984) in a four-week Business English program at the University of Guelph. The authors explore how the stages of Kolb’s experiential model informed the design of experiential activities in a Business English program. In addition, the authors discuss how experiential learning contributes to raising students’ language proficiency and cultural awareness and to furthering understanding of business concepts studied in class. The article concludes with the description of some challenges of the application of the model as identified by the students and the teachers, as well as highlights pedagogical implications of the use of the experiential learning model in a second language classroom.

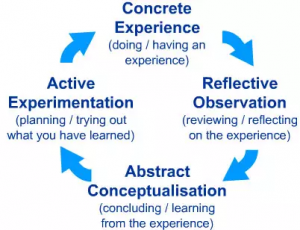

Experiential learning is an important component in higher education learning models found in co-ops, practicums, and classroom tasks that simulate work experiences. In his explanation of the importance of experiential learning, Kolb (2015), drawing upon the ideas of Dewey, James, Lewin, Rogers and others, believed that “learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (p. 49). Kolb played an important role in developing the experiential learning approach and presenting it visually in the Experiential Learning Cycle, which underpins most pedagogical approaches to this type of learning. His learning cycle has four stages as demonstrated in Figure 1.

When describing each stage Kolb (2015) explains that “immediate or concrete experiences are the basis for observations and reflections. These reflections are assimilated and distilled into abstract concepts from which new implications can be drawn. These implications can be actively tested and serve as guides in creating new experiences” (p. 51). Therefore, to learn from an experience, it must be placed in a cycle of learning where the experience is reflected on, analyzed, and tested. This is evident in most definitions of experiential learning offered by colleges or universities. For example, the University of Guelph defines experiential learning as “a pedagogical practice whereby students gain new knowledge, skills and abilities by intentionally applying their classroom learning in a workplace or simulated workplace setting. Experiential learning opportunities are grounded in an intentional learning cycle with clearly defined learning outcomes” (“Experiential Learning at the University of Guelph,” n.d.).

International students who need language practice in English face an additional challenge of experiential learning. According to Kohonen (1992), for courses primarily focused on language learning, experiential learning can provide many opportunities for authentic communication, reflection on the experience and language structures used, and feedback on those language structures. He also adds language learning elements to Kolb’s learning cycle to demonstrate how language learning could take place within the model. Knutson (2003) also believes experiential learning could be used to help students learn a second language effectively because learners focus on the co-creating of meaning when completing a task-based activity or in-class project and not on discrete items of the target language. Knutson also recognizes that the opportunity for self-reflection could help language learners “negotiate social meaning and their own shifting identities in a new culture” (p. 63). Consequently, the experiential learning approach allows students to work on their language learning goals while actively engaging in and reflecting on their learning before, during and after the concrete experience within the learning cycle.

Although experiential learning is primarily an individual learning process, for all learners to benefit from the opportunity, educators should ensure that the four stages of the experiential learning cycle are well scaffolded to include all learners. According to Walsh, Rutherford, and Sears (2010), writing about an experiential-based course developed at the University of Calgary, “critical to the success of the course was the opportunity to engage in experiential learning with members of the population of interest and courses should be designed in ways that support meaningful inclusion. Course instructors should consider the diversity of learners when developing the curriculum and should seek to implement supports and procedures to minimize the potential concerns and problems while maximizing opportunities for novel learning” (p. 206). When working with international learners, this support of diversity could include language support for a variety of proficiency levels. This is the focus of the Business English Program at the University of Guelph where language and culture support for Japanese University students are added to experiential learning opportunities with local businesses.

Description of the Business English Program

The Business English Program (BEP) has been running for six years in the English Language Programs at the University of Guelph. It is a four-week intensive program for the Japanese students from Doshisha, Kansai, and Musashino universities. The students are from different academic backgrounds and are at various English proficiency levels. This program focuses on developing students’ English language communication skills, cross-culture awareness, and understanding of business concepts in a Canadian context. Based on the needs analyses conducted with the students and administrators from the three Japanese universities, key topics have been selected for BEP, a few examples of which are presentations, marketing strategies, business email writing, job search, and interviewing. The highlights of this customized program are volunteer opportunities, company visits, and guest speakers from local businesses. The in-class and out-of-class experiential activities, assignments, and assessments based on Kolb’s (2015) learning cycle provide the students with an authentic, engaging, and language-rich environment for language learning and a deeper understanding of business concepts in a Canadian business context. These curricular activities help students integrate language, culture, and business concepts and maximize their learning experiences by following the four stages of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation of the New Experience, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation.

Concrete Experience

In this stage, the BEP students visit a local business. The instructors provide Company Visit Worksheets with guided questions for the students to use before, during, and after the visit. Before the visit, the students research the company using guided questions and prepare their own questions about the company. During the visit, students listen to a presentation, take notes, participate in Q&A sessions, observe company operations, and interact with company employees. The instructors provide language support, such as feedback on the prepared questions and industry-specific vocabulary lists and expressions to help students understand the presentation and to interact with company staff in a professional manner.

Reflective Observation of the New Experience

During this stage, students reflect on their experience of visiting the company by noticing business concepts studied in class, sharing their observations of Canadian business practices, and linking them to their own knowledge about Japanese companies. In the instructor-provided worksheets, students record their general impressions from the company visit, identify the differences between Japanese and Canadian businesses in similar industries, and provide suggestions that may benefit Japanese and Canadian companies. In addition, in a discussion forum created on an LMS (CourseLink), the students post their reflections about the impressions from the company visit and respond to their peers’ discussion posts. They share their learning experience from the company visits and reflect on how it improves their understanding of Canadian culture and business concepts they have learned in class.

Abstract Conceptualization

In addition to sharing their reflective observations of the company visit on the discussion forum on CourseLink, the students work in pairs to complete a formal presentation in class using presentation and language skills to connect their on-site visit experience to business concepts studied in class. The instructor gives face-to-face and online feedback and evaluates the discussions and presentations. This process deepens the students’ understanding of the abstract business concepts that they have learned in class and experienced during the company visit. Some of the business concepts students focus on are SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, the marketing mix, and product USP (unique selling proposition) (Bickhoff, Hollensen, & Opresnik, 2014). Through the analysis of the information obtained from observations and interactions during the company visit and feedback from instructors and peers, the students further their understanding of abstract business concepts.

Active Experimentation

In this stage, the students apply a newly acquired understanding of business concepts and language structures from the previous stage to complete a capstone project, which is a marketing analysis of a Japanese product that students want to bring to the Canadian market. Students need to identify marketing mix, SWOT, and the product USP, as well as to provide a rationale why this product would attract potential investors in Canada. This capstone project not only provides students with the platform to apply their internalized business concepts but also offers opportunities for them to practice language skills and demonstrate their awareness of cultural differences.

Opportunities and Challenges

The design of the company visit experiential learning activity in the BEP affords students the opportunity to get first-hand experience of engaging in and reflecting on the learning of both business concepts and language structures studied in class. The students exploit this opportunity by researching a company’s products and business practices, interacting with a company’s employees, and then reflecting on their experience. Consequently, the experience of visiting a company expands the learners’ knowledge of the business concepts from the course as well as provides the learners with valuable language practice.

Some of the challenges faced by students while participating in experiential learning activities relate to their different learning needs and the short and intensive nature of the program. The learners in the program come from different academic fields; therefore, their prior knowledge of the business concepts varies. Students’ language proficiency levels range from beginner to high intermediate (A1 to C1); as a result, some students have a more difficult time communicating during the visits and have to rely on the observations and support of their peers. Regardless of their proficiency levels, all students identified the challenges of understanding technical vocabulary and fast-paced connected speech. Additionally, the students stay in Canada for only four weeks and are introduced to many business concepts during in-class and out-of-class activities, which they have to internalize and practice in a short time.

The instructors in the program have observed another challenge related to interaction patterns during the visits. The students are reluctant to ask questions in front of the whole group during the visit, yet they are comfortable interacting with the company employees in smaller groups. Even though the questions are prepared and practiced ahead of time in class, the students prefer to ask them individually while interacting with company employees rather than during a post-visit Q&A session. Such interaction patterns may be culturally influenced and may relate to existing interaction patterns in a students’ home country.

Pedagogical Implications

Experiential learning activities have far-reaching pedagogical implications. To bring real educational value to students, experiential learning activity needs to be tailored to students’ needs. It has to be scaffolded to include a variety of activities that nurture the development of students’ language, culture, and content understanding. If designed with the learners’ needs in mind, experiential learning activities can contribute to a better understanding of complex business ideas, provide a platform to practice language, and help students develop an appreciation of a new culture.

References

Bickhoff, N., Hollensen, S., & Opresnik, M. (2014). The quintessence of marketing: What you really need to know to manage your marketing activities. Heidelberg: Springer.

Experiential Learning at the University of Guelph. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.uoguelph.ca/experientiallearning/about-el/experiential-learning-university-guelph

Knutson, S. (2003). Experiential learning in second-language classrooms. TESL Canada Journal, 20(2), 52–64.

Kohonen, V. (1992). Experiential language learning: Second language learning as cooperative learner education. In D. Nunan (Ed.), Collaborative Language Learning and Teaching, (pp. 14–40). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kolb, D. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education.

McLeod, S. A. (2017, October 24). Kolb’s Learning Styles and Experiential Learning Cycle. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html

Walsh, C.A., Rutherford G.E., & Sears, A.E. (2010). Fostering inclusivity through teaching and learning action research. Action Research, 8(2), 191–209.

Author Bios

David Siefker is a Lead Instructor in the English Language Programs at the University of Guelph in Canada and has taught in a variety of programs including business English and teacher training for over 25 years. He has a Master’s in Applied Linguistics and is interested in how higher education teaching practices can be applied to second language pedagogy. He can be contacted at dsiefker@uoguelph.ca.

Ling Hu is a Lead Instructor in the English Language Programs at the University of Guelph in Canada. She has an MEd in Organizational Studies and BA in English Language Teaching. She has been an EFL/EAP/ESL professional for more than 20 years with a special interest in needs-based English language curriculum development that fosters meaningful collaborative and autonomous learning. She can be contacted at

lhu@uoguelph.ca.

Nataliya Borkovska is a Lead Instructor at the University of Guelph English Language Programs. She has an MA in TESOL and an MA in TEFL. Nataliya has been dedicated to English instruction for the past 20 years. Her main areas of professional interest lie in second language pedagogy, teacher education and development, educational leadership, specialized vocabulary instruction, and the use of technology in language teaching. She can be contacted at nborkovs@uoguelph.ca.