“Challenge is an integral part of transformative experience”; I came across this line in “Unsettling Faculty Minds: A Faculty Learning Community on Indigenization” (Yeo et al., 2019, p. 38). It resonated with me because this has been true in my life. Challenge usually precedes and instigates change, whether that change is internal or external. However, despite the momentum produced by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the recent acknowledgment of the treatment of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women as genocide, there still remains resistance among educators to answering the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action.

It is important to recognize that universities, including my own, the University of Toronto, have acknowledged the role they played in the erasure of Indigenous culture and the justification of cultural genocide. Universities and colleges across Canada have begun responding to that Call to Action by developing strategies for Indigenization and hiring Indigenous professors. Indeed, an entire Spring issue this year (2019) of New Directions in Teaching and Learning was devoted to the topic of Indigenization in Canadian institutes of higher education.

Yet, when it comes to integrating Indigenous perspectives or issues into the ESL curriculum, there remains resistance, discomfort, and ambivalence about the place of such material within English language teaching. Some teachers say they are not comfortable teaching this material. Their difficulty confronting this subject matter might be attributed to defensiveness about entrenched beliefs, blindness to them, or to white fragility, a term coined by Robin DiAngelo to describe “the disbelieving defensiveness white people exhibit when their ideas about race and racism are challenged, or when challenged about complicity in racist systems of privilege” (cited in Waldman, 2018). Settlers may find ways to evade confronting their own participation in colonial systems, what is called a move to innocence. These can include denying settler status by locating colonialism in the past or by identifying with a group distinct from the British and French nations who participated in post-contact historical events (Lowman & Barker, 2019). Another attitude often expressed is that teachers do not know enough about the topic to teach it and its corollary, that only Indigenous people should teach this material. None of these arguments, as we shall see, are valid. I will address these points throughout this article.

Faced with this resistance, I have asked myself why I believe so strongly that there is a need to Indigenize ESL curriculum. What is my knowledge based on? How do I hold myself accountable? In other words, what are my reasons for doing this, and how can this translate into action? In the course of my reading, I have encountered many terms new to me, such as white fragility, decolonization, environmental racism, settler identity, equity literacy, epistemic ignorance, and pedagogy of place, to name a few. I have also been reading material recommended to me by Brenda Wastasecoot, Assistant Professor at the Centre for Indigenous Studies at the University of Toronto. But I must emphasize that I am only at the beginning of this journey, and I have much more to learn. So, I share with you some of what I have managed to synthesize over the last few years.

I should clarify that this article is not primarily about communicating what Indigenous content to include in the ESL classroom. Instead, it is a polemical piece, exploring the reasons why we should incorporate Indigenous voices and perspectives into our ESL/EAP curriculum, what the challenges are, how to avoid certain pitfalls, and suggestions for best practices. To address this topic, I will need to make clear some assumptions and beliefs that underlie my argument. For instance, the sources I have consulted in researching Indigenization in higher education, specifically in an ESL or EAP context, argue that it is not merely about teaching content (such as Residential schools or treaties) nor is it an add-on, something superfluous or “subordinate that detracts from more important information to be taught”, which Dewar (1998, p. 17) found was the reason behind some teachers’ reluctance to implement this material. Let us begin with a definition.

What is Indigenization?

According to one definition, “Indigenization recognizes the validity of Indigenous worldviews, knowledge and perspectives”. It identifies “opportunities for Indigeneity to be expressed” such as incorporating “Indigenous ways of knowing and doing” (“A brief definition of decolonization and Indigenization”, 2017). Moreover, Marlene Brant Castellano (2014) adds that it examines “how and to what extent current content and pedagogy reflect the presence of Indigenous peoples and the valid contribution of Indigenous knowledge”.

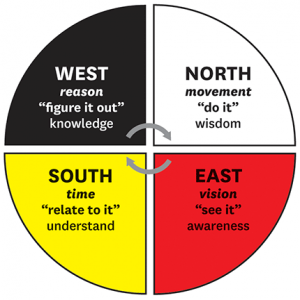

One such element that has been identified as a pedagogical tool is the teachings of the medicine wheel, which can “provide an educational framework that can be applied to any educational setting” (Bell, 2014). “Moving from linear models to the interconnectedness of the circle can guide the development of pedagogy and vision for the future” (Graveline as cited in Bell, 2014). The Medicine wheel, an important symbol and source of knowledge for Indigenous peoples, can be divided into many types of quadrants representing, among other things, the four directions, the four seasons, the stages of life, and types of knowledge. Movement in the Medicine wheel begins in the East and travels clockwise towards the North. One division of the Medicine wheel that I have found useful is shown in Figure 1: Gifts of the Four Directions. Thinking about Indigenization requires self-reflection or vision, an understanding of history or time, reason which incorporates knowledge, and ultimately, action or accountability, which is informed by wisdom. As Vaudrin-Charette (2019, p. 113) acknowledges, “accountability is central in Indigenous perspectives”; “one of the flaws of our systems of higher education is a tendency to decouple awareness of injustice from the responsibility to challenge justice” (Pitawanakwat as cited in Vaudrin-Charette, 2019, p. 113).

Figure 1: Gifts of the Four Directions

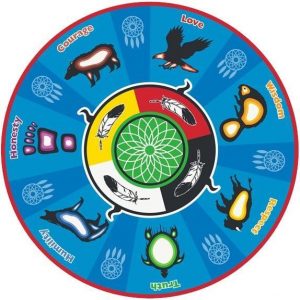

Figure 2: Seven Grandfather Teachings

In 2015, the TRC Calls to Action specifically urged educators at Canadian universities and colleges, as well as other levels of education, to “integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods in order to build student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy, and mutual self-respect”. In addition, they asked that educators “engage with skills-based training in intercultural competence, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism” (TRCC: Calls to Action, 2015, p.7). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has important implications for all of us, including ESL educators.

Why Now?

Amy Abe states insightfully: “We will always be learners, not masters, in the journey. If we wait to become masters we will never begin” (2017, p. 32). This reminds us that for the vast majority of ESL teachers who are settlers, not Indigenous, this is a life-long journey of learning. We are not the experts. However, we can become allies. As such, we need to seek input from Indigenous colleagues and Elders.

Now more than ever in the geo-political-environmental climate we inhabit today, teachers need to include in their classrooms diverse worldviews and new ways of knowing, seeing, and experiencing the world. We know that our culture is often invisible to us, and yet it shapes our thoughts, our values, and our actions. Adichie (2009) in her TED Talk warns of the dangers of only interpreting others’ lives through the single preconceived story we impose on them.

Wade Davis argues in his TED talk (2003) that the world is losing diversity in ethnospheres (the diverse cultural web of life in the world since the beginning of consciousness) at an even greater rate than species in the biosphere. (Sadly, he may no longer be correct in this statistic.) However, this does not diminish his example of the loss of 50% of the 6000 languages spoken in the world within the last fifty or so years.

Speaking of the biosphere, that brings us to another reason for why now? We are living in an increasingly polarized world, which Davis claims “300 years from now, is not going to be remembered for its wars or its technological innovations, but rather as the era in which we stood by and either actively endorsed or passively accepted the massive destruction of both biological and cultural diversity on the planet” (2003).

This is relevant because as Vaudrin-Charette states, “Indigenizing is not strictly cultural. It is also ecological, economical, relational, and essential to our species’ survival” (2019, p.113). For thousands of years, First Nations and Inuit practiced sustainable use of and sharing of resources. It is pretty clear that they have something to teach us.

Assumptions and Beliefs

As I have been learning about Indigenous worldviews, I have come to realize that the Western academic approach emphasizing reading or knowledge alone is not enough. Or to clarify, what our Western viewpoint traditionally constructs as knowledge is insufficient. In the Indigenous worldview, the deepest knowledge comes from the heart.

So, my belief in the value of Indigenizing the ESL curriculum is rooted in a commitment to being an ethical educator: that along with demonstrating respect for our students, part of our role as teachers is to expose students to issues of injustice, inequity and racism, and to both model and offer opportunities for intercultural understanding, self-reflection, critical thinking, and different perspectives on what constitutes knowledge and how we see the world. As ESL teachers, we are never just engaged in teaching the technical elements of language. Teaching language, we know, involves teaching culture. During the U.S.A’s wars and invasions in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, the code name for enemy territory was Indian country, and Geronimo was the code name for Osama bin Laden (Tuck & Yang, 2012, pp. 31-32). As we know, words have power. This is true whether we speak from a culture rooted in oral narrative or from one dominated by the written word. Language is never neutral. When we speak or write, even if we are unaware of it, we always do so from a certain social and political standpoint. Language is political, and by extension, so is language teaching. What we omit speaks as loudly as what we include.

Critical pedagogy teaches us that the classroom is a locus of power dynamics. Whether we acknowledge it or not, teachers hold a position of power. What we learn from reading about decolonization, a necessary step in the process of reconciliation, is that colonialism is not just situated in the past but is replicated in the present through our institutions, ideologies, and epistemology. Settlers are not only those who were born in Canada, but include anyone, including immigrants, who participate in the colonial culture and benefits from it (Lowman & Barker, 2015). As a result, we need to examine how we may inadvertently be contributing to perpetuating this in our teaching. For instance, do we portray Canadian history as a mythic Canadian narrative of heroic struggle and the establishment of a just and distinct society? Do we uncritically offer up Stephen Harper’s or Justin Trudeau’s apologies to residential school survivors without analyzing the subtext?

Teachers have an obligation to offer a more intercultural, inclusive, equitable vision of society and to help learners recognize, critique, and consider how systems of inequity can be redressed. Both teachers and students need to investigate and recognize their own participation in othering. If we expect our students to develop critical thinking skills, we must be willing to examine our own biases and myths and demonstrate how we reflect on and investigate them. Students are future leaders and potential agents of change. We do not know how what we teach may impact them, but we can be sure it will one way or another.

Land Acknowledgements and Position Statements

We are used to hearing Land Acknowledgments being read at the beginning of conferences and meetings. Best practices dictate that Land Acknowledgments should be more than just a recitation of a script. They should be personalized to include one’s own commitments to action and accountability. In my reading about Indigenous perspectives, I discovered the importance of including a Position Statement: in addressing reconciliation, it is important to situate oneself contextually in terms of one’s identity and how it influences, biases, or affects one’s understanding and outlook on the world. It speaks to an obligation for action by settlers like me to redress what has been taken away from Indigenous peoples. This begins with the land.

Appallingly, the government has failed to address conditions on First Nations reserves, the consequences of Industrial projects that impact traditional lands, waterways, drinking water, and overall health, including birth defects from toxic chemicals. In contrast, I recognize that I am privileged to have access to safe drinking water, good educational opportunities within my community, safe housing, and adequate healthcare.

Colonialism persists in Canada’s institutions, such as schools, which consistently fail Indigenous youth by removing them from their communities. It also exists in prisons, which incarcerate Indigenous peoples in disproportion to their population. A United Nations committee found that an Indigenous youth is more likely to end up in prison than to graduate high school (Restoule, 2017). The effects of colonialism impact Indigenous people’s life expectancy, rates of poverty, suicide rates, and food insecurity. As a settler, I am complicit in this colonial system.

Racism continues to pervade Canadian society and has led to and continues to lead to assimilation, discrimination, violence, rape, and the murder of Indigenous peoples. While as a woman, I am more likely to encounter violence than a white man is; a U.N. report on violence against women found that an Indigenous woman is 3 times more likely to encounter violence than I am (as cited in Brake, 2019). I recognize that as I encounter institutions such as schools, the justice system, and healthcare, I will not suffer this same racism due to my privileged position.

Moreover, many Indigenous communities living on reserves also suffer from environmental racism, which is defined as environmental injustice that occurs in practice and in policy within a racialized context.

I feel compelled to address these both personally and as an educator. I would like to be considered an ally who has a responsibility to contribute to the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action as best I can. As Justice Murray Sinclair stated about the Calls to Action in the TRC report, “education got us into this mess and it will take education to get us out of it” (as cited in the Assembly of First Nations, 2013).

But how do we go about integrating Indigenous voices and perspectives into our curriculum in a way that does not reflect tokenism, decontextualized content removed from historical events, or marginalization of the real issues, and yet also doesn’t focus on victimhood as the sole defining characteristic of how we view Indigenous peoples?

Indigenous worldview vs Colonial worldview

Wilson and Nelson-Moody (2019, p. 54) ask: “What is the benefit of our institutions professing to produce interculturally competent global citizens if we are ignoring or erasing the very voices needed for greater intercultural problem-solving?” Much of what is summarized in these next two sections comes from the ongoing Coursera course taught by Jean-Paul Restoule on Aboriginal Worldviews and Education, delivered through OISE (Restoule, 2017). Indigenization requires incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing and doing and recognizing these as valid. We must recognize that Indigenous worldviews differ from Western colonial worldviews in many significant aspects and that these have played a role in the suppression of Indigenous peoples’ rights and culture. The colonial worldview has at its core a belief that land ownership is private, while Indigenous peoples view the land as a shared environment. Western attitudes view the land as an object to be exploited, and its resources extracted, while Indigenous peoples view the land as a teacher, something animate and connected to people.

In the Western colonial view, time is seen as linear, which supports the belief that civilization progresses developmentally along a linear path, and Indigenous peoples were located along this spectrum as less developed and in need of civilizing. In contrast, Indigenous peoples depict time as cyclical as illustrated by the medicine wheel. This predominant use of the symbol of a circle representing interconnectedness in Indigenous epistemology contrasts with the Western linear adoption of hierarchy. Non-linear thinking is able to produce new ideas and understanding by thinking laterally or combining systems, putting different ideas together and creating new knowledge. The emphasis on relationality and relationships resembles ecosystem thinking. It contrasts with the Western scientific approach, which studies discrete parts of the external world by examining isolated variables.

Indigenous Knowledge and Teaching Methods

The Indigenous worldview has implications for the characteristics of Indigenous knowledge and methods of teaching. For example, knowledge is not assumed universal but contextual and personal. Sharing of knowledge is bound up in relationships in which the teacher assesses the seriousness and readiness of the learner. Knowledge is not something possessed but something that exists in relationship to others and other entities in the world. The method of teaching relies on the principle of non-interference or indirect instruction. Knowledge is derived from experiential learning, which impacts methods of teaching. Learners are provided opportunities to experience things for themselves. Since there is no division between nature and culture, both are available as teachers. Indigenous languages prioritize action, and verbs come first. Experiential learning uses verb forms to discuss types of experience. In contrast, Western knowledge is noun-based, and stability or permanence resides in the object. In Indigenous knowledge and teaching, oral transmission is paramount and has as much power as written transmission. Storytelling is a primary mode of learning through narrative and connecting through the stories we share. As the medicine wheel demonstrates, Indigenous knowledge is holistic and focused on restoring balance. The sources of Indigenous knowledge also differ because they include not just content, but also traditional knowledge such as values and beliefs that are passed on from Elders. The sources of knowledge are much more empirical, being drawn from the experience of our senses and from traditional ecological knowledge. Finally, the sources of knowledge include revealed knowledge found in dreams, signs, fasting, and visions of purpose (Restoule, 2017). Lafever argues that this spiritual dimension is lacking from Western categorizations of knowledge, such as Bloom’s taxonomy, which includes only cognitive, physical, and affective domains, whereas the Medicine Wheel includes all four (2016, p. 416).

Cautions/Considerations

ESL teachers must be careful to avoid decontextualizing Indigenous experience from history and also ensure they are avoiding the cultural appropriation of symbols, teachings, art, dress or any other relevant aspect. Moreover, one must recognize that while there are certain commonalities in an Indigenous worldview, Indigenous peoples are diverse and should not be depicted as a monolith. In sourcing materials, we should allow Indigenous people to speak for themselves and avoid speaking for them. In fact, we should consult with Indigenous colleagues and educators as a check on the integration of Indigenous material into our curriculum and invite them into our classrooms. Decolonization is not a metaphor but is a response to the historical reality of colonization (Tuck & Yang, 2012).

Another challenge is the risk of “portraying Aboriginal cultures and Aboriginal people as merely part of the multicultural mosaic in which everyone can partake and everyone is equal [which] belies the very violent colonial processes through which this land has become a ‘multicultural nation’” (Dion, Johnston, & Rice, 2010). The authors of the report warn against a diversity training approach, which emphasizes prejudice management rather than engaging in an analysis of how colonialism has created systemic inequality in Canadian society. A multicultural approach to oppression does not address Indigenous sovereignty or rights to self-determination. We must also be careful not to adopt a victimhood perspective, while still acknowledging the cultural and literal genocide inflicted by government policies such as Residential schools. For this reason, it is considered best not to begin with these topics. While avoiding the idealizing of Indigenous peoples in a romantic stereotype, we should recognize the contributions and sophistication of Indigenous civilizations, as well as critically examining the myths of civilization and progress that justify settler colonization and occupation of land.

Best Practices

I will conclude with some suggestions from several authors whom I have cited, along with some of my own, on ways to develop a Pedagogy for Reconciliation, a term coined by Jeremy Siemens (2017).

- Engage in Professional Development workshops facilitated by Indigenous facilitators to learn more about Indigenous history, issues, and worldviews. These should be mandatory for all educators.

- Compare mainstream and Indigenous views on historical and current events (Freeman et al., 2018).

- Privilege Indigenous authors and speakers in order to reverse the erasure of Indigenous voices and incorporate Indigenous cultures, histories and worldviews into the curriculum (Freeman et al., 2018).

- Make use of traditional talking circles (Abe, 2017;)(First Nations Pedagogy Online, 2009)

- Adopt storytelling, a fundamental Indigenous teaching approach, as a way to engage in language learning (Abe, 2017).

- Make explicit the power relationships in language. E.g. the use of the passive voice and present perfect to distance oneself from blame (Abe, 2017); (Walsh-Marr, 2019).

- Identify values and assumptions or infer biases and motives in texts/culture (CLB outcomes as cited in Abe, 2017).

- Approach texts/textbooks with a critical eye (Abe, 2017).

- Examine what we know and how we know it (e.g. research methodology) and compare Western and Indigenous systems of knowledge-making.

- Avoid binary oppositions: the tendency of Western thought to see the world or solutions to its problems as either/or dualities.

References

A brief definition of decolonization and Indigenization. (2017). Working Effectively with Indigenous Peoples Blog. Retrieved from https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/a-brief-definition-of-decolonization-and-indigenization

Abe, A. (2017, August). Indigenization in the ESL classroom, TESL Ontario Contact Magazine, 43(2) Retrieved from http://contact.teslontario.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/contact_2017_02.pdf

Adichie, C. N. (2009, July). The danger of a single story. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks chimamanda_ adichie_ the_ danger _of_a_single_story

Assembly of First Nations (2013). Communique from the National Chief Shawn Atleo. Retrieved from https://www.afn.ca/2013/11/04/communique-from-the-national-chief-shawn-atleo-november-4-2013/

Bell, N. (2014, June 9). Teaching by the medicine wheel: An Anishinaabe framework for Indigenous education. Education Canada Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.edcan.ca/articles/teaching-by-the-medicine-wheel/

Brake, J. (June 27, 2019). UN report highlights systemic violence against Indigenous women, supports MMIWG inquiry findings. Retrieved from https://aptnnews.ca/2019/06/27/un-report-highlights-systemic-violence-against-indigenous-women-supports-mmiwg-inquiry-findings/

Castellano, M. B. (2014, June 10). Indigenizing education. Education Canada Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.edcan.ca/articles/indigenizing-education/

Chung, S. H. (2019) The courage to be altered: Indigenist decolonization for teachers. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 157(2), 13–25.

Davis, W. (2003, February). Dreams from endangered cultures. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/wade_davis_on_endangered_cultures

Dewar, J. M. (1998). Non-Aboriginal teachers’ perspectives on teaching Native studies. (Unpublished Master’s thesis). University of Saskatchewan. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Retrieved from http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/SSU/TC-SSU-06182007141808.pdf

Dion, S., Johnston, K., & Rice, C. (2010). Decolonizing our schools: Aboriginal education in the Toronto District School Board. A report on the urban Aboriginal education pilot project. Retrieved from https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/Community/docs/Decolonizing%20Our%20Schools%203.pdf

Freeman, K., McDonald, S., & Morcom, L. (2018, 24 April). Truth and reconciliation in your classroom. Education Canada Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.edcan.ca/articles/truth-reconciliation-classroom/

First Nations Pedagogy Online. (2009). Talking circles. Retrieved from

https://firstnationspedagogy.ca/circletalks.html

Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek/Gull Bay First Nation. (2019). 7 grandfather teachings. Retrieved July 22, 2019 from

http://www.gullbayfirstnation.com/7-grandfather-teachings/

King, T. (2012). The Inconvenient Indian: A curious account of Native people in North America. Toronto: Doubleday Canada.

Lafever, M. (2016). Switching from Bloom to the Medicine Wheel: Creating learning outcomes that support Indigenous ways of knowing in post-secondary education. Intercultural Education, 27(5), 409–424.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2016.1240496

Lowman, E. B. & Barker, A. J. (2015). Settler identity and colonialism in 21st century Canada. Halifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Reid, R. E. (2019). Intercultural learning and place-based pedagogy: Is there a connection? New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 157(2), 77–90.

Restoule, J. P. (2017). Aboriginal Worldviews and Education. Coursera, video lecture, Toronto, viewed October 2017.

https://www.coursera.org/learn/aboriginal-education

Siemens, J. (2017). A pedagogy of reconciliation: Transformative education in a Canadian context. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education, 8(1), 127-135. Retrieved from

https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjnse/article/view/30803

Sims, T. (2018). 7 Grandfather Teachings. Prepared for Ska:Na Family Learning Network, Windsor, Ontario. Retrieved from https://clubrunner.blob.core.windows.net/00000000608/en-ca/files/homepage/7-grandfathers/7grandfathersaug2018.pdf

Talaga, T. (2017) Seven fallen feathers: Racism, death, and hard truths in a Northern city. Toronto: House of Anansi Press.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Calls to action. Retrieved from http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Tuck, E. & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

Vaudrin-Charette, J. (2019). Melting the cultural iceberg in Indigenizing higher education: Shifts to accountability in times of reconciliation. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 157(2), 105–118.

Waldman, K. (2018, July 23). A sociologist examines the “white fragility” that prevents White Americans from confronting racism. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/a-sociologist-examines-the-white-fragility-that-prevents-white-americans-from-confronting-racism

Walsh-Marr, J. (2019). An English language teacher’s pedagogical response to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 157(2), 91–103.

Williams, H. (2019). Towards being inclusive: Intentionally weaving online learning, reconciliation, and intercultural development. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 157(2), 59–76.

Wilson, J., & Nelson-Moody, A. (Yexwulla, T.). (2019). Looking back to the potlatch as a guide to truth, reconciliation and transformative learning. New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 157(2), 43–57.

Yeo, M., Haggarty, L., Wida,W., Ayoungman, K., Pearl, C. M. L., Stogre, T., & Waldie, A. (2019). Unsettling faculty minds: A faculty learning community on Indigenization, New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 157(2), 27–41.