Abstract

Language Instruction for Newcomers to Canada (LINC) aims to advance both newcomers’ English language learning and their settlement skills and goals. Canada’s official languages, cultural awareness, and employment and settlement skills are essential drivers of settlement and a core part of the LINC curriculum. In response to these needs, Blended Learning (BL) LINC programs combine face-to-face (f2f) LINC classes with online activities beyond the classroom and integrate technology and settlement skills with English language learning. BL provides learners with essential opportunities for developing their English skills while learning the digital skills necessary for effective settlement in Canada.

At the 2019 TESL Ontario Conference, LINC and ESL teachers and administrators raised important questions about BL and our research regarding the effects of BL in LINC (Cummings, Sturm, & Avram, 2019). Some wondered what to do about students who voice their preference for the traditional language learning model without technology integration; others asked about the implementation of technology and what digital skills support settlement and learning English. We discuss these questions and make a case for BL in this article. First, however, as background we review research findings regarding the effects of BL in LINC as presented at TESL Ontario on December 5, 2019: Cummings, Sturm, Avram; TESL Ontario Conference Presentation, 2019.

Background: The Effects of Blended Learning in LINC

BL provides f2f classroom instruction combined or “blended” with online and other computer-mediated activities (Kennel & Moriarty, 2014). From September 2017 to June 2018, in response to the paucity of research about BL in settlement language learning contexts, we conducted a demonstration research project with a BL LINC program in British Columbia to examine the effects of BL for students and teachers.

This project was carried out with 45 intermediate LINC students, three of their instructors, the program manager and resource support teacher. An established LINC program that had implemented BL effectively since 2012 was selected as the research site according to a demonstration research approach. A demonstration project examines real applications of innovations in progress in order to extrapolate possible extensions to other contexts. The school board program presented as an effective, well-developed model of blending learning for English language instruction and TELL (technology-enabled language learning) that has the potential for adoption, extension, and adaptation to various LINC/ESL contexts.

Research Questions and Methodology

Three questions were the focus:

- What were the effects of the BL approach for the students’ English language learning and for their participation in LINC?

What were the effects of the BL approach for students’ self-efficacy and knowledge for using technology for language learning? - What were the effects of the BL approach for LINC teachers, instruction, and the program?;

- What effective or “best” practices for BL were demonstrated in this context?

BL was examined through a variety of research activities to gain multiple perspectives on its effects:

• CELPIP Testing provided a baseline description of each student’s language proficiency at the beginning.

• Student Questionnaire and Interview: A background questionnaire and 30-minute semi-structured interview provided insights about students’ perceptions of BL.

• Teacher/Staff Questionnaire and Interviews: A background questionnaire and 45–60 minute teacher interview provided insights about the effects of BL and teaching practices.

• A Student Self-Efficacy Questionnaire about Using Technology: The questionnaires showed students’ perceptions about their abilities for using technologies for their learning and identified areas of confidence and anxiety.

• Observations and Collection of Tasks/Artefacts: Classroom and online observations of activities provided data for description of BL. Tasks and artefacts from PBLA (Portfolio-Based Language Assessment) were collected as examples of language improvement.

• Student Focus Group Discussions: Focus group discussions regarding the effects and benefits and challenges of BL classes were done near the conclusion. Students assumed the role of researchers by recording their focus groups’ BL experiences.

Data were analyzed using methods of constant comparison. Interpretations were compared to reach inter-rater agreement. Representative quotes from the participant interviews and questionnaires are included here to illustrate the findings and themes. PowerPoint slides from the Focus Groups are also included as representative artifacts from the research.

Blended Learning Approach

What the Research Site Was Like

The research project was conducted in three BL LINC classes at a school board program in British Columbia—two daytime classes, a LINC 6 and a LINC 7/8, and one evening LINC 7/8 class. The two daytime classes met three days in class and one day online; the evening class was two days f2f and two days online. The tech base consisted of laptops and iPads. Students had access to free WiFi and often used their own devices. Before starting in any of the blended classes, students completed a Transition to BL class (25-30 hours of instruction) where they were introduced to BL, some basic EduLINC features, and PBLA, and completed PBLA About Me activities online.

All three classes used EduLINC, the LINC 1 to LINC 7 courseware for settlement language training classes across Canada. Additional digital tools were used to develop specific skills and support project work. The online and classroom activities were interdependent, and both teachers and students emphasized the importance of this interdependence. The teachers applied the principles of “flipped learning”, meaning that students often worked on the content at home in advance of classes. When in class they could therefore focus on communication and collaborative activities. However, communication and collaboration, both with the teacher and classmates, were also characteristic of many of the online activities. Online teacher presence and student engagement were considered essential ingredients for success.

What the Teachers Did Online

Teachers focused on learning outcomes, content selection and development, assessment and evaluation, student engagement, integration of online with f2f activities, and activity and progress monitoring. For the teachers, it was highly important to set clear expectations about the students’ participation in the online component right from the start. Details about learning outcomes, deadlines for assignment completion, and assessment methods were communicated to students. Teachers also raised awareness of successful online learning strategies and developed activities to support them. The built-in EduLINC activities online were used to various degrees, mostly customized to fit the specific context and needs of each class. As the teachers developed their skills for online teaching and digital technologies, they started creating new content and e-materials in response to student needs. They also curated and facilitated access to a variety of online resources that students could explore at their own pace to support the students in achieving their study, community and settlement goals. Digital tools to support language learning and community connections such as Quizlet and QR Code Reader/Generator were also introduced with opportunities for the students to use them in a meaningful way. All was coordinated with the in-class activities.

Students explained the effects of these resources/tools and the online activities:

• Freedom/flexibility (time and place)

• We keep learning every day. Whenever we have free time, we can access our account in

EduLINC and learn.

• Online Activities give us more resources and topics to explore

(Batgirl, Arli, Sailor Moon, Kelly; Focus Group)

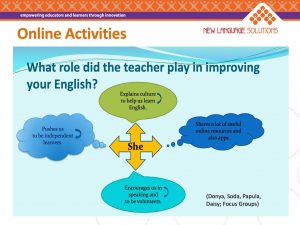

• [The teacher] shares a lot of useful online resources and also apps

(Donya, Soda, Papula, Daisy; Focus Group)

Finally, teachers ensured their online presence was strong in order to engage and support students. Teachers guided, monitored, modelled online behavior, answered questions, encouraged, and provided feedback. They also used the data they collected to inform their overall planning and the integration of online and f2f activities.

Figure 1: What role did the teacher play in improving your English? (**Images may be more clear in the PDF version.)

What the Students Did Online

• Students’ roles were as varied and complex as the teachers’ roles. Students practiced language skills through online activities that supported digital skill learning critical to their settlement process. Many of the activities replicated real-world tasks or prepared the students for them.

• Students regularly accessed online resources curated by the teacher. They selected and used those relevant to their needs; for example, they explored educational, community, and employment resources such as volunteer opportunities, training programs, or resume and interview workshops. LINC 6 learned how to access resources and engage with the community through Twitter. One participant (Cinderella) indicated “the twitter block [gave them] a chance to understand how the people and organization connect[ed] together in Canada.” Students also learned how to research and evaluate resources themselves and then recommended the most relevant ones to their classmates. Students even created learning content with the teacher’s guidance.

Current events were accessed and then discussed online or in class. Students appreciated the opportunity to share ideas and opinions. As Cinderella noted: “Third, I can learn from each other by sharing our writing assignments online. It is a big difference from the f2f class. When I was in f2fclass, I can not learn from other classmates’ articles. But when I am in the blended class, we have a good place to share our writing. I can read and learn some new vocabulary or idea.”

• Collaborative project work both online and in class was common, especially in the higher levels. LINC 7/8 in particular worked on projects that involved not only collaboration among the students in class, but also with the whole school and some community organizations; for example, the students applied for small neighbourhood grants used for school community building and also organized family sponsoring by the school at Christmas time. Students valued each other as sources of knowledge and support; they taught, helped, and listened and gave advice to each other, both online and in class. The online communication with each other and the teacher supported the development of soft skills for effective communication both in online and offline mediums.

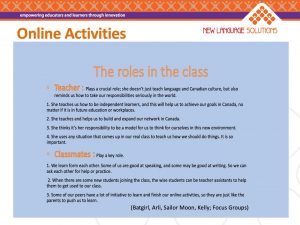

Figure 2: What roles did your peers play in improving your English? (**Images may be more clear in the PDF version.)

Portfolio-Based Language Assessment (PBLA) in Blended Learning

• The nationwide teaching and assessment approach in LINC is informed by PBLA. The PBLA processes were consistently integrated and co-ordinated with the online and in-class activities. There was a high degree of interaction between BL and the implementation of PBLA. As Eleanor (Teacher) mentioned: “It is impossible to separate PBLA in any way—the requirements for PBLA drive the development of all class activities…We have monthly topics and I assess student needs, then develop skill building and using activities that will build to assessments. Any portion of this process can occur online.” Many of the online activities became PBLA artefacts.

• Some PBLA activities were facilitated by the online component. Needs assessment, goal setting, self-reflections, and feedback often took place online. Online exemplars and success criteria for different types of activities and tasks were also available to students in a teacher-generated Reference Resources Glossary in one of the classes. This was one of the most accessed online resources, and some students asked if they could continue to have access to it after they left the class. Access to settlement resources was also facilitated with sections in EduLINC dedicated to this.

• Student activity in EduLINC was a rich source of information on student progress and engagement with learning, and tracking tools facilitated access to the relevant data. This was especially useful when writing the student progress reports. In preparation for the teacher-student conferences, students also used the online space. Eleanor’s students completed online checklists to make sure their portfolios were ready for teacher review. Andrada’s students reviewed Can Do Statements and reflected on their progress in an individual wiki, an activity they were already familiar with; the regular reflections helped students engage actively in their learning and develop metacognitive skills.

Findings: The Effects of Blended Learning

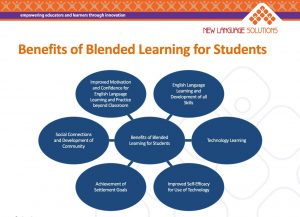

This research showed BL:

- improved access to LINC classes and participation by students;

- improved student attendance, satisfaction with the program, retention, and engagement;

- increased interaction and reduced sense of isolation;

- increased use of English and students’ ease in using English to pursue settlement goals;

- enhanced access to technology and increased students’ confidence for using technology for learning English and achieving their settlement goals.

Figure 3: Benefits of Blended Learning (**Images may be more clear in the PDF version.)

Participation, Access, and Interactions

BL improved access and student participation. Students chose BL because it allowed them to work part time outside the home or at home with family while studying English. The administrator noted that monthly attendance in BL classes was higher than attendance in other classes: “In one BL class with EduLINC, average attendance is 95 % plus; 89 % across all [blended classes]” (Gladys, Program Administrator Interview). Teachers explained:

“Attendance is really good… Students seem to look forward to sharing what they’ve done online and learn more in class…” (Andrada, Teacher Interview)

Donya explained: “…because I have to look after my family, I can’t be a full-time student in school all week long. I use a few days learning in the class, talking with my classmates to practise my oral language and listening…to participate in this program makes me feel free in study” (Donya, Student PBLA artefact).

Ana (Student Interview), like Donya and many others, appreciated the interactions and connections that BL created: “…online offers lots of opportunities for interaction. The flexibility is great… you choose when you want or have time to do the work.”

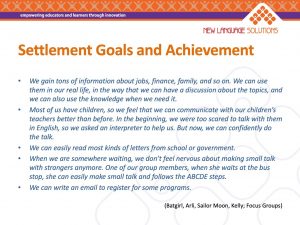

Improved English Language Learning and Settlement Skills

Students’ English language learning and increased confidence in using English for achieving their settlement goals were noted by both the students and teachers.

Students explained how f2f combined with online learning benefited them:

To tell the truth, the blended learning program is quite new for me. Since I never took any online classes. In-person classes provide us the opportunity to talk to others as well as help us improve writing skills and reading strategies. While on-line classes provide us more classes to do the practice. I like blended learning since I work daytime, on-line classes allow me to finish the assignment also take care of my family. We have different topics each month which are helpful for newcomers to get to know Canada as well as to improve our English skills.

We feel like online class and taking class at school is connected. We would prepare for the class at school because of the online class. Some programs (example: Quizlet, typing.com…) can use only online. It helps learning…We can check and review online. We could learn more details by ourselves.

The experience of students learning English and working on their settlement goals was highly positive. The BL approach allowed students to access learning in a customized way that responded to individual needs, interests, and schedules and developed their learning in these ways:

Figure 4: Settlement Goals and Achievement (**Images may be more clear in the PDF version.)

• Development of independent learning skills through BL: Students emphasized opportunities for learning digital skills and thus being able to learn more independently through BL. SweetCoco2 (Student Interview) noted: “The first day of class, I was shocked. I realized I didn’t really have the skills.” She explained that she got the skills she needed for Canadian society in the BL class and that she hoped it would help her get a job. SweetCoco2 added: “No more running away from the technology! …being able to use technology is not a choice anymore.”

• Familiarity with technology, online learning modes, and social media: Students indicated that BL classes helped them to improve their use of technology for learning English. Jin (Student Interview) explained that she could find out about grammar more quickly using EduLINC and that she used a dictionary app on her phone to look up words. Other students noted how the access to technology for learning English helped them with their settlement. Aleesa (Student Interview) explained how she used computers for real life communications in BL activities: “…buying and selling things; searching for community events/ medical services; education for my daughter; communications with my case manager; activities in chat rooms such as What’s App, Facebook, Messenger, Viber; listening to the news or Ted Talks; reading different articles and press releases; communication about volunteer work, the Work B.C. program; communicate with service providers such as B.C. Hydro…”

• Accessibility and flexibility of BL: Students noted that the BYOD policy and practice supported their learning. Abraham (Student Interview) explained that he relied heavily on his smartphone for learning English and about the community. He read the New York Times because he was interested in politics, and listened to music in English, and used Google Maps. He added: “I am hungry for information – after all the restrictions in the first country.”

Self-efficacy and Knowledge for Technology Use

Students completed a questionnaire rating their self-efficacy for using technology. Responses showed that most students gave a high rating for their confidence to do a variety of online tasks. However, some students were uncertain about finding information, specifically about housing and education, submitting online applications, and online learning. These areas are directly connected to newcomers’ settlement goals and may indicate their anxiety about doing these higher stakes activities online.

Effects for Teaching

The teachers echoed the students’ advocacy of BL in LINC. They highlighted increased opportunities for engaging with and supporting students in their English language and settlement learning, as well as timely feedback and support for students, and the integration of in class and online activities and learning.

Teaching/learning activities improved as the integration of technology and EduLINC activities provided multiple opportunities for student practice. Online learning and the use of technologies both online and in class meant that a variety of tasks, media, and resources were available for activities and communications with students – audio and video recording for speaking/listening activities, presentations, and feedback; discussion forums for analysis and practice; wikis and blogs for reading and writing. And teachers noted how the combination of f2f and online learning enhanced the integration of PBLA tasks and increased opportunities for students to work on and develop artefacts for their portfolio assessments. Andrada (Teacher Interview) explained: “Blended learning transcends the classroom walls; it’s engaging and creative; it connects [students and teachers] with the larger community; it breaks the potential of isolation of traditional, classroom-based language learning; it’s flexible. It’s also sometimes challenging – as a teacher using this approach you have to update skills and knowledge continuously. You become a learner yourself, which I love.”

The teachers also noted challenges with BL. They highlighted the need for more designated professional development time to support ongoing teacher development and training for blended learning, as well as designated time for their collaboration on curriculum and online activities. Ultimately, they recommended the provision of a larger, more formalized professional community of practice in which to develop blended learning knowledge and practice.

- Best Practices and Conditions for Blended Learning

This research project demonstrated basic practices necessary for BL to thrive—important information for other programs. These include: - Stable wi-fi and consistent and sufficient technology support

- Sufficient portable devices on campus

- A Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) policy and practice

- Experienced and knowledgeable LINC teachers enthusiastic about and professionally developed in using technology and EduLINC

- Leadership by administration to provide the technologies, childcare, other resources, and support for teachers

- Transition to blended learning classes for students

- Ongoing professional development and training for teachers

- Consistent teacher-student engagement and interaction with students (teacher presence) – online as well as in the classroom

- Integration of PBLA activities into the blended learning program/curriculum and PBLA activities in the online activities

Discussion

We now address questions about BL raised by teachers and administrators at the TESL Ontario Conference and make the case for BL in LINC. How can LINC programs address the reservations and challenges of newcomers who are sceptical about BL? What do newcomers need in order to achieve their settlement and English language learning needs? How can BL assist newcomers adapt to the realities of life in Canada? We make the case that both language and digital skills are important elements of LINC students’ settlement projects. The BL approach and research explained above demonstrate how BL provides learning opportunities that benefit both students and teachers. Programs, teachers, and students need to consider these benefits of BL.

1. Blended language learning is flexible and adaptable:

BL accommodates a variety of learning styles. Preferences for a learning style may affect learner motivation. BL engages learners with content in a variety of ways, online and offline. The BL research project showed that presenting content in a variety of ways not only keeps learners motivated but also increases outcomes because learners are exposed to content in a variety of ways, offering opportunities for preparation, review, repetition, and adaptation. BL enables more personalized learning. It increases motivation because topics and tasks are engaging – they are relevant to students’ lives.

• BL supports diverse needs of students’ lives and schedules, allowing students at “higher levels” to continue to study by choice. We have seen in this BL project how blended learning can improve access and participation in LINC. However, this need not be limited to “higher LINC levels” as LINC students at lower levels benefit from BL with the appropriate supports. The Transition classes in this project illustrate that it is important to prepare learners so they can use online learning resources, e.g. EduLINC, more independently. Transition classes to BL classes and other supports make the benefits of improved access available for a wide range of LINC level learners and reduce the challenges for those reluctant to use technologies.

2. BL encourages and enables independent learning:

• Independent learning does not mean students are on their own in BL. It’s self-paced and connected, in class and online. BL supports learner autonomy and self-reflection. Teacher presence and engagement with students both f2f and online is an important factor in BL.

• As we noted from the research findings, students complete most individual activities online; it leaves time for communication and interaction when f2f so that students and teachers reap the benefits (in other words, “flipped” models of teaching/learning).

• BL eases independence and the transition out of LINC 8 by building a resource base for practice outside of the classroom. BL supports independent learning skills because teachers are not immediately present f2f at all times. Students overcome their anxiety about what will happen after they leave the LINC program and develop autonomy and connections to a wider community.

3. BL builds digital citizenship skills:

• It develops and expands digital literacy and real-world skills.

• It supports students in accessing resources and services online.

• Students develop needed multi-modal literacy and digital skills.

4. BL lowers anxiety levels:

• Students engage online in more thoughtful discussions as they have time to craft their responses.

• Students have opportunities to review and repeat activities as often as they need outside of the classroom.

• Students come prepared to work and interact at school because they have opportunities to engage with the content before class time.

• Students have more choice about how they learn, when they learn it, and when they practice what they have learned.

• Students who need to attend to family and other obligations can keep up and catch up with their peers.

• Students are more connected to their teacher and their peers. Peer and teacher support is an important feature in BL inside and outside the classroom.

• Students build networks with their peers that support their settlement process during and after the LINC program.

5. BL improves attendance, engagement, and retention: Higher motivation and participation through online and offline engagement with various content activities catering to a variety of learning preferences is a definite benefit of blended learning.

6. BL supports teachers:

• The role of the teacher as a facilitator, model, and leader in the classroom and online is strengthened. The BL research demonstrated that teachers engaged consistently with students to guide them in what they needed to learn both in terms of English and settlement resources and goals; also, they modelled pronunciation, speaking, body language and gestures, and effective English language usage. The role of the instructor in BL is key to the achievement of students. BL requires teachers to be centrally involved and engaged with their students to facilitate the learning/teaching that they need.

7. BL expands access to information and knowledge:

• Not only does BL improve access to information (web 1.0), but it also improves participation and collaboration (web 2.0). Learners benefit from online participation, which is especially important as many services and communications that newcomers need to access are moving to online delivery (e.g. government services, communication with schools….)

Conclusion

The BL research project demonstrated considerable benefits for LINC students’ participation in LINC, for their English language learning, and for students’ self-efficacy and knowledge for using technology for learning and achieving their settlement goals. Teachers explained numerous advantages for instruction and student learning. Effective or “best practices” and conditions needed for BL to work became evident; as well as challenges still to be addressed.

Questions about BL and how to implement it effectively such as the questions raised by teachers at TESL Ontario are important. Continuing this discussion is essential and further action research is needed. The BL demonstration research project showed the potential for this approach. Mainly, we need to provide more BL opportunities for newcomers to develop their English language while learning the digital skills necessary for settlement in Canada. BL in LINC provides this dual advantage for our learners.

Links to resources

• Research Report: https://learnit2teach.ca/wpnew/learnit2teach-publications/

• TESL Ontario 2019 Conference session slides: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/t0w463i8t1l3ypw/AABotpvw44RFGYtm-7QlI2vta?dl=0&preview=T5K-BLdemoproject_rev13_Nov.+29+for+TESL+Ontario.pptx

• Tutela webinar playback re: “Researching the Effects of Blended Learning in LINC” – Log into Tutela. https://tutela.ca/ first; then https://tutela.ca/Event_31832

References

Cummings, J., Sturm, M., & Avram, A. (2019). The effects of blended learning in LINC: A LearnIT2teach Demonstration Project.

https://learnit2teach.ca/wpnew/reports/Demo_Project_Evaluation_Report_WEB.pdf

Kennell, T., & Moriarty, M. (2014). Adult settlement blended language learning: Selected annotated bibliography.

http://learnit2teach.ca/wpnew/moodle_2_5_bib/LIT2T_Bibliography_WEB_2014.pdf

Author Bios

Dr. Jill Cummings is Associate Dean of Faculty Development with Yorkville University, Canada. Jill completed her PhD in Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning/Second Language Education at the University of Toronto. Jill researches issues related to innovation and creativity, online and blended learning/teaching, the Communities of Inquiry framework, and teacher knowledge and instruction. Her edited book, “Creative Dimensions of Teaching and Learning in the 21st Century” (Cummings & Blatherwick, Editors. 2017. Brill Sense.) focuses on innovations in education across a range of disciplines and levels.

Matthias Sturm is an independent researcher and evaluator for the LearnIT2teach project. Matthias also is working towards a PhD in the area of digital equity at Simon Fraser University, Canada. For many years, he has supported service providers in adult education and immigrant settlement in their efforts to build program capacity.

Augusta Avram is an educator interested in the impact technology has on the way we learn, communicate, and share our voices. During her long career in education, she has fulfilled a variety of roles, with those of teacher and researcher being the favourite ones. For the past few years, she has been working mainly with newcomers.