Abstract

Racism in education has a long 500-year history with colonial roots that situates knowledge production as a Western prerogative. Colonizers intentionally created an educational system based on Eurocentric epistemologies that promoted White supremacy. Pieterse & Parekh (1995) argue that in the 20th century, capitalism and industrialization enabled global oppression and resurgent nationalism which undermined social justice initiatives. Over the last thirty years in Canada, despite increasingly diverse students, inclusive curricula, and equity policies from elementary schools to universities, the teacher and administrator workforce has remained racially homogenous. Learning English has become an intrinsic part of a global post-colonial legacy in which many continue to perceive the ideal educator to be White males. Currently, microaggressions among ESL teachers and exclusion in decision making reflect ongoing racism. Deconstructing colonial education and critiquing the reproduction of systemic racism against Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) is necessary to advocate for decolonizing English language learning.

Introduction

Prior to colonization, centers of higher learning in Africa were established in Morocco, as early as the 9th century and later in what is now Mali and Egypt in the 16th century. However, Western style schools eventually usurped local African communities as knowledge producers (Anabila, 2017). The original intent in providing basic literacy and math skills to non-White subjects, was to serve colonial interests that would enhance labor exploitation (Altbach, 1971; Falola, 2018). Grants obtained from colonial powers were more regular than church tithes and provided stable funding. In fact, colonizers made a “selfish calculation…that training Africans for positions that Europeans could occupy was in effect creating a revolution that would destroy the system” (Falola, 2018, p. 551) that supports White supremacy. As a rationalization for colonization, African cultures were demonized to the West (Falola, 2018). Educational institutions constructed under colonialism offered substandard education that ensured the colonized learned enough to comply with their imperial dominators but not enough knowledge to lead to insurrection (Altbach, 1971; Falola, 2018; Pieterse & Parekh, 1995). Students who aspired to post-secondary education, were forced to attend universities in Europe (Falola, 2018). Established in 1943, higher learning centers in Africa were actually called “colonial universities” (Falola, 2018, p. 605). Educational institutions continue to reproduce systemic racism utilizing a pedagogy of oppression (Freire, 1970) created by colonizers.

Today, there are many postcolonial epistemologies: critical pedagogy, democratic schooling, equity pedagogy, multi-cultural, anti-racist and social justice education, such as the Jesuits’ liberation theology, critical Frankfurt School tradition, and Critical Race Theory (Swalwell, 2013). But distinguishing between knowledge and understanding is essential because learning about racism may not necessarily lead to empathy (Swalwell, 2013). In fact, when confronted with systemic racism, people may go through various emotional reactions (Henry et al., 2017) such as the commonly known Kubler-Ross stages of grief: 1) Denial – “I don’t see color. I just see the person.”; 2) Anger – “I am not racist! You are because you are dividing us by color.”; 3) Bargaining – “All people are racist. If I went to your country, people would discriminate against me.” “White people are now being judged.”; 4) Sadness – “I thought we were better than this.”; 5) Acceptance – “I need to do something to help.” False equivalencies are another attempt to deflect and deny racism in Canada. There can be the perception that Canadians are less racist than Americans. An assertion that persists even though Americans have elected a Black president, twice, and a Black South Asian female Vice-President. Teaching about residential schools, mass graves and the indifferent treatment towards missing and murdered Indigenous women can help deconstruct Canadian exceptionalism. Given the current cruel practice of law enforcement taking Indigenous men from public roads at night and dropping them off in isolated areas in the frozen north, known as “Starlight Tours,” there has never been a more important time for abolishing colonial legacies.

However, many educators assume that the West was built on meritocracy rather than the genocide of Native communities, racial exploitation, and capitalist patriarchy creating barriers for equity. There are reservations about associating with stigmatized groups, disdain for racial accommodation and belief in self-determination (Eisenberg, 2013). Economic contexts also influence attitudes towards immigrants increasing “xenophobic violence against migrants and refugees in times of austerity” (Henry et al., 2017, p. 9). While equity programs and offices have proliferated in number over the last two decades, senior university administrators across Canada have grossly underrepresented racialized staff, specifically women of color in a climate of neo-liberalism which may be as low as 2% of faculty (Henry et al., 2017). Abella (1985) as cited in Henry et al. (2017), argues “the issue is about removing barriers to their equal participation, which will not occur without enforceable and systemic intervention” (p. 11). James and Chapman-Nyaho (2017) found that “Canadian universities’ commitment to equity and diversity has decreased and diversity hiring has, at best, stalled” (p. 85). The wheels of equity grind extremely slowly.

Rather, through Canadian systems, such as the immigration policy, settler colonialism is perpetuated (Jefford, 2018). Immigrants to Canada have always struggled to survive among increasingly hostile environments in public spaces, education, and employment. Back in the mid-1990s, a new type of affluent skilled worker began arriving in Canada (immigration.ca, 2019). A few years before 1997, Hong Kong businessmen and their families immigrated to Canada under the Business Class as Britain’s lease over Hong Kong was ending. Concerns over financial stability once Hong Kong went back to China was the primary factor in precipitating the large influx into Canada. It was the first time in Canadian history that incoming immigrants were more affluent than Canadian born Canadians (Gzowski, 1990). Hong Kong immigrants kept the Canadian economy afloat during the 90s recession, often buying houses and cars in cash. Among the earliest immigrants from Hong Kong was Li Ka-shing, who bought out the Vancouver and Toronto waterfront railway lands and developed them into prime real estate over the next few decades. As of January 2021, Mr. Ka-shing stands as the 30th richest person in the world (Jacob & Rogers, 2019). Even though not every Hong Kong immigrant was affluent, the income gap between Asian newcomers and Canadian born Canadians created feelings of resentment (Gzowski, 1990). In areas such as Vancouver, housing prices were driven up by the newcomers, making homeownership difficult for domestic buyers. Today, China ranks as having the second highest number of millionaires (Ponciano, 2020) and billionaires (Tognini, 2021) in the world. In 2016, China was also one of the highest numbers of sending countries to Canada for international students who overall brought 15.5 billion in spending dollars and created over 165 000 jobs (Government of Canada, 2018). Unfortunately hate crimes in Vancouver increased by 717% against the Chinese community during COVID (Zussman, R., 2021, Feb. 18) as anti-Asian racism rises.

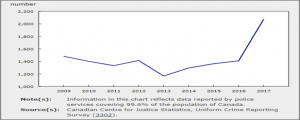

Even places of worship are no longer exempt from hate crimes. On September 12, 2020, a fifty-eight-year-old Muslim worshipper was murdered just outside a Rexdale mosque. Video evidence shows a man creeping up and fatally stabbing the volunteer custodian, Mohamed-Aslim Zafis in the back. Since 2016, hate crimes in Canada have spiked due to increasing nationalist xenophobia.

(Slack, 2018)

(Slack, 2018)

Many service provider organizations for newcomers such as the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants (OCASI) and neighborhood HUBS funded by the United Way and various government agencies, offer settlement services with anti-racist policies, grounded in Critical Race Theory and anti-oppressive framework. Workshops on empowering immigrants in employment, leadership opportunities in their communities and public places to speak in their mother tongues are some of the services offered. In contrast, English language education, as the lingua franca, continues to function as a means of assimilation, rather than integration for newcomers today. Shortly after the last residential school closed in the late twentieth century (de Costa, 2017), ESL classes expanded. Bill C-24, a Harper government initiative, requires citizenship applicants between the ages of 14 – 65 to have “adequate knowledge of one of the official languages of Canada,” (Canada, 19 June 2014) echoing residential school requirements. ESL program delivery remains dismayingly focused on the technical, rather than social justice aspects of language learning. A societal paradigm shift fostering a more racially democratic society is required where educators prioritize eliminating systemic oppression.

Systemic racism in education

The post-colonial legacy impacts all education systems in terms of institutional, social, and professional oppression. Even though the James and Chapman-Nyaho (2017) study was conducted in the Canadian university context, there are parallels and potential applications for ESL program delivery. Participants in the James and Chapman-Nyaho (2017) study consisted of forty-five females and forty-four males, racialized and Indigenous professors, working in small, mid-, and large-sized universities, in all disciplines in various contracts to tenured faculty. 5 major themes emerged:

- Culture of Whiteness – Maintains color blindness, institutional inertia, and tokenism.

- Hiring friends – Racialized women are not offered tenure and passed over.

- Systemic Inequity – Equity policies do not address resistance to diversify because there is no accountability for implementation.

- Good intentions – While initially the scales may tip in favor of some diverse candidates, once they were hired, many felt ambivalent about how they were perceived by White colleagues who were not shy about pointing out they were inclusion hires.

- Color kills careers professionally and personally – Where racialized faculty attempted to create change in the department through taking leadership positions, White faculty undermined their authority.

Further, racialized women tend to be clustered in the most precarious jobs at universities (Henry et al., 2017) and other educational contexts. Education management continues under the shadow of an oppressive post-colonial legacy of keeping racialized educators in their subordinate place while reproducing White supremacy.

Decolonizing institutions and management

For these reasons, immigrant education managers have an important role in leading decolonization efforts. Britzman and Pitt (2004) discuss how trauma can be used to inform pedagogy based on difficult knowledge. While decolonization refers to the literal, political and metaphorical processes of intellectual criticism, Western neocolonialism perpetuates stereotypes of the South and East, therefore “decolonizing the imagination is the relationship between power and culture, domination and the imaginary” (Pieterse & Parekh, 1995, p. 4). Consequently, decolonizing initiatives in education have sought to encourage racial and cultural identity exploration, foster a desire to return to a dignified pre-colonial existence and escape Western hegemony (Fanon, 1968). Linking history and pedagogy can result in developing significance through symbols to challenge the “cultural dynamics of ignorance and forgetting as a defense against knowledge” (Britzman & Pitt, 2004, p. 356), essential to developing a new disruptive pedagogy. Given the number of human rights violations and genocides around the world, difficult knowledge is one that must be a part of inclusive education where new knowledge can clash with existing assumptions creating anxiety and even pedagogical meltdowns (Britzman & Pitt, 2004). Di Angelo (2011) describes spurious reactions of White fragility where some claimed they felt physically ill when discussing racism and White privilege. Stewart (2014), a Canadian professor who is Black, notes he always felt like a visitor due to his skin color while White Europeans are seen as members. Discussions on colonial impacts on learning can result in trauma on both sides. On the colonized side, there may be great internalized oppression resulting in learned helplessness while pro-assimilation educators can resist relinquishing White privilege and Eurocentric hegemony.

Systemic change should be a priority because changing structures is much easier than changing people (Fullan, 2000). In February 2020, Durham Region came under fire for their Black History Month Scavenger Hunt activities which included dancing to reggae and talking to a person who is Black (Westoll, 2021). Trivializing the Black experience demonstrates it is vital to include diverse voices when planning events, creating policies, and disciplining infractions. A major step would be the inclusion of racialized supervisors in ESL service provider organizations. As more diverse management teams lead in language learning, hopefully their input will be received with respect. Committees should be diverse, representing demographics of most ESL learners which tend to be racialized women. Through working with diverse staff, teachers who are White and middle class, can learn to improve their “cultural competence” (Ladson-Billings, 2001, as cited in Haque & Morgan, 2009, p. 272) and develop strategies to implement “identity pedagogies” (Haque and Morgan, 2009, p. 282). Unfortunately, equity detractors can often resort to calculated condescension, racist double standards, and outright sabotage in meetings to silence diverse voices. As a result, racialized staff in predominantly White institutions can be easily othered and marginalized by bullying from ESL administrative assistants, custodians, teachers, and managers. Even when diversity is not welcome at the decision-making table (Ibrahim, n.d.), BIPOC teachers should seek management roles. Representation matters.

Stewart (2014) offers some supportive advice for racialized educators that can resist internalizing oppression leading to learned helplessness. Create an anti-racist support group. Be aware of privileges offered to others. Ask questions. Don’t accept being wrong or perceived as too sensitive. Allow for a margin of error. An important further action should be to take a census of staff in educational institutions. While American educators have a long history of keeping race-based data, Canadian institutions have lagged. Census data can reveal a need to bridge the divide among the powerful White male decision makers in reproducing privilege. Returning to the practice of involving communities in schools (Arabila, 2017) and hiring BIPOC helps diverse students see themselves reflected in school personnel and demonstrates power sharing (Jefford, 2014). Oddly enough, even though the public school system requires principals to have taught various grade ranges in their respective elementary and high school streams, there are minimal expectations of classroom experience for ESL supervisors and managers. Neoliberal ideologies, Whiteness and re-masculinization dominate in hiring practices “that largely restrict hiring to individuals’ capacity to fit in, to be liked, and/or to not cause ‘discomfort’ for those already inside the institutions…Therefore, efforts to have a diverse population of faculty members is more about image. It means bringing in individuals who ‘look different’ into institutions ‘to add colour’ while keeping Whiteness in place” (James & Chapman-Nyaho, 2017, p. 90). Recently, Portfolio-Based Language Assessment (PBLA) curricular changes have required supervisors to have a working familiarity with curriculum implementation, causing management to tacitly reveal their lack of knowledge through voluntary retirements and the necessity of hiring leads.

Decolonizing the teacher workforce

Sharing narratives about faculty experiences can be an effective strategy in dealing with racism (Stewart, 2014) at all levels of education. Haque and Morgan (2009) engage in dialogue reflecting on a national desire for global cosmopolitanism, instrumental need for English language learning and the “racialized imaginary of English speakers” (p. 271) situated by gender and race. When newcomer demographics shifted thirty years ago, ESL classes expanded in the late 1990s to accommodate the influx of immigrants into Canada. ESL instructor demographics, as a teacher workforce consisted mainly of White Canadian born female baby boomers who tended to be homemakers or Ontario Certified Teachers. Yet, (Ladson-Billings, 2001 as cited in Haque and Morgan, 2009), notes most White, middle-class teachers, “have never experienced being a visible or political minority, and they are often unaware of how race, class, and gender have influenced their circumstances or perspectives” (p. 272). The prevailing belief was that if you could speak English, you could teach it. However, “in order to develop ‘cultural competence…white teachers need to learn about their own identities and privileges in order to deal with the kinds of systemic barriers that their minority students face” (Ladson-Billings, 2001, as cited in Haque & Morgan, 2009, p. 272). Currently, there are very few discussions in ESL classrooms and curricula on how to deal with individual and systemic racism. Students can avoid creating discomfort for White teachers by putting on a disingenuous face that life in Canada is happy and safe despite hate crime evidence to the contrary. Students are not receiving support in dealing with racism in Canada through ESL program delivery, highlighting the importance of hiring diverse social justice educators. Like educators in colonial universities, ESL teachers are trained to pass on just enough language skills to serve Canadian settler colonial agendas based on national labor needs.

Further, racialized female ESL teachers, as a postcolonial legacy, may not receive the same deferential courtesy associated with professional educators. Rivers and Ross (2013) note that managers, staff, and students are aware of the challenges faced by teachers of color in immigrant education. There is a preference for the ideal ESL teacher to be a straight male with blond hair and blue eyes (Haque & Morgan, 2009; Rivers and Ross, 2013). Despite an increasing racially diverse teacher workforce with international experience, there are still very few ESL educators who are Black. There are also social barriers in acceptance as a non-White person despite first language fluency (Ibrahim, n.d.) and qualifications that are equal to or greater than White male counterparts. Haque & Morgan (2009) observed that racialized female teachers were under pressure to demonstrate competence and professionalism as opposed to building egalitarian rapport with ESL students. In Canada, English language learning occurs in the context of a fictitious multiculturalism, classroom disrespect and suspicion when non-White teachers challenge Eurocentric texts and practices (Haque & Morgan, 2009). The prevailing ideology supports White supremacy as the ideal people, lifestyle and knowledge producers and views non-White cultures and educators with a pejorative lens (Jefford, 2014).

Decolonizing texts

Altbach (1971) explains that neocolonialism is not direct control as in the past, but rather an indirect retaining of domination through planned policies and texts, specifically in education. Teachers with Western biases continue to promote White supremacy by utilizing colonial textbooks, curricula, and administration patterns. Even Ethiopia and Liberia, which were not colonized in the traditional sense, have come under Western influence through foreign aid resulting in reproducing neocolonialism (Altbach, 1971). In this way, education makes it possible to disadvantage BIPOC people and maintain global Eurocentric hegemony. Post-colonialism has been touted, but “white-supremacist culture wants to claim the entire agency of capitalism” (Spivak, 1995, p. 183). Nonetheless, postcolonial sensibilities must be developed that can develop complex and fluid transnational identities (Pieterse & Parekh, 1995; Szanton Blance et al., 1995). Rather than perpetuating the reproduction of East/West colonization, a syncretic approach rooted in forging a global perspective with local connections may be a superior alternative in constructing a postcolonial identity (Pieterse & Parekh, 1995). Subverting colonialism requires acknowledging that not only were intellectuals in formerly colonized countries drained of all content and form, but their philosophies and beliefs were distorted. For these reasons, ESL instructors should use contemporary materials that reflect the racial identities of the learners in a positive light, to deconstruct colonial stereotypes.

Reading texts that glorify a White settler Canada and situate the colonizer as heroic subjects, can cause racialized students and staff to internalize the colonial voice, reproduce racism and become complicit (de Beauvoir, 2011) in their own oppression. Discourse on imperialism situates the West as the Subject and continues to relegate non-Europeans as the shadowy Other whose knowledge is continually subjugated, disqualified, and ignored by imperialistic legacies (Bhabha, 1995; Spivak, 1983). Mukherjee (1986) offers an example of how students can ignore the racial, social, and political contexts when given classroom materials with the dominant voice that enables the belief that human beings face similar dilemmas, leading to internalizing the very ideas that oppress them. Christian (1987) discusses the notion that “there has been takeover in the literary world by Western philosophers from the old literary elite…(who have) the power to be published and thereby determine the ideas which are deemed valuable, some of our most daring, and potentially radical critics (and by our I mean black, women, third world) have been influenced, even coopted, into speaking a language and defining their discussion in terms alien to and opposed to our needs and orientation” ( p. 457). Spivak (1983) also notes that male hegemony can create silence on categories of race, class and gender as subsumed into one category. ESL classes appear diverse while suppressing racially conscious voices with a dearth of representative texts.

Subverting colonial assumptions must challenge established knowledge, authority, and power based on White supremacy. Eurocentrism is now becoming an increasingly identified and acknowledged site of privilege (Swalwell, 2013). The conscious subaltern voice can be seen as a counter narrative to the dominant colonial groups (Spivak, 1983). There is a tacit expectation that epistemologies produced by Western/Northern academics are assumed to be universally relevant and applicable, while Eastern/Southern epistemologies are limited by race and geography (Falola, 2018; Said 1978). However, the complexity of post-colonialism requires praxis in transnational literacy willing to hear different voices other than the traditional White European male (Spivak, 1995). Literary criticisms and philosophies should include “intersection of language, class, race, and gender in literature” (Christian, 1987, p. 458). Indeed, using English literature texts that are from one racial origin enables students who are White and middle class to bask in smug superiority while multicultural students may relate superficially to the text, if at all (Spivak, 1983). Including authentic immigrant narratives, cultural traditions and national histories can create a classroom climate of equity and respect that resists colorblind multicultural constructs. There should be greater expectations for all involved in immigrant education to learn about positive contributions to global knowledge from formerly colonized countries.

Conclusion

Working in conjunction with the ideologies and policies of newcomer immigrant centers who effectively engage with ethnic enclaves to inform their practices, it may be possible to move away from the oppressive Euro-centric legacies of the past, move towards a post-colonial paradigm and ultimately decolonize Canadian education. In a climate of ongoing culture wars, notions of civic responsibility should be expanded to include elements of global citizenship. In other words, anti-racist best practices should not remain at the shallow level of festival multiculturalism, eating samosas and drinking chai lattés. There are currently some social justice programs in terms of Holocaust Education and increasing efforts at Indigenizing curricula. But without diverse leadership, ESL programs can be seen as echoing tragedies in Canadian history when hegemonic decisions were made without ever consulting Native communities, resulting in linguistic, cultural, and racial genocide. Similarly, at the Berlin Conference (1884 – 1885) European colonizers divided Africa without any Africans at the table (McClintock, 1995). ESL service providers need to take lessons from history, learn from their immigrant settlement services counterparts and reject reproducing oppressive colonial practices. Diverse materials, inclusive curricula, and racial heterogeneity that represents local communities in all decision-making processes are the most essential aspects of anti-oppressive management. Decolonizing education remains one of the most important tasks for educators in the 21st century.

References

Altbach, T. (1971). Education and neocolonialism. In B. Ashcroft, G. Griffiths, & H. Tiffin (Eds.), The Post-Colonial studies reader. Rutledge.

Anabila, C. (2017). Recollections of past events of British colonial rule in northern Ghana, 1900-1956. In S. el-Malik & I. Kamola (Eds.), Politics of African Anti-Colonial Archives. Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.

Bill C-24: Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014). 1st Reading, Feb. 6, 2014, 41st Parliament, 2nd Session. Retrieved from the Parliament of Canada website:

https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/41-2/bill/C-24/royal-assent/page-30#2

Bhabha, H. (1985). Signs taken for wonders. In B. Ashcroft, G. Griffiths, & H. Tiffin (Eds.), The Post-Colonial studies reader. Rutledge.

Britzman, D., & Pitt, A. (2004). Pedagogy and clinical knowledge: Some psychoanalytic observations on losing and refinding significance. JAC, Special Issue, Part 1: Trauma and Rhetoric, 24, (2), 353–374. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20866629

CBC (2018, Sept. 18). Man charged in stabbing death of Etobicoke mosque caretaker. CBCNews. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/man-charged-death-mosque-caretaker-1.5730329

Christian, B. (1987). The Race for Theory. In B. Ashcroft, G. Griffiths, & H. Tiffin (Eds.), The Post-Colonial studies reader. New York: Rutledge.

de Beauvoir, S. (2011). The second sex. (C. Borde & S. Malovany-Chevallier, Trans.) Vintage Classics.

de Costa, R. (2017). Discursive institutions in non-transitional societies. International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique, Special Issue: Reconciliation, transformation, struggle, 38(2), 185–199. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26556890

Dei, G. J. S., James, I. M., Karumanchery, L. L., James-Wilson, S., & Zine, J. (2000). Removing the margins: The challenges and possibilities of inclusive schooling. Canadian Scholars’ Press.

DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54–70. https://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp/article/viewFile/249/116

Eisenberg, A. (2013). Identity politics and the risks of essentialism. In P. Baling & S. Guerard de Labour (Eds.), Liberal Multiculturalism and the Fair Terms of Integration. Palgrave Macmillan.

Falola, T. (2018). The Toyin Falola reader on African culture, nationalism, development and epistemologies. Pan-African University Press.

Fanon, F. (1968). National culture. In B. Ashcroft, G. Griffiths, & H. Tiffin (Eds.), The Post-Colonial studies reader. Rutledge.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Fullan, M. (2000). The three stories of education reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(8), 581–584.

Government of Canada. (2018). International Education: Economic impact of international education in Canada. https://www.international.gc.ca/education/report-rapport/impact-2017/sec-5.aspx?lang=eng

Haque, E., & Morgan, B. (2009). Un/Marked pedagogies: A dialogue on race in EFL and ESL settings. In R. Kubota & A. Lin (Eds.), Race, culture and identities in second Language education: Exploring critically engaged practice. Routledge Inc.

Henry, F., Enakshi, D., James, C., Kobayashi, A., Li, P., Ramos, H., & Smith, M. (2017). The equity myth: racialization and indigeneity at Canadian universities. UBC Press.

Ibrahim, A. (n.d.). Will they ever speak with authority? http://www.academia.edu/227859/Will_They_Ever_Speak_With_Authority?

immigration.ca. (2019). Established immigrants wealthier than Canadian counterparts, study shows. https://www.immigration.ca/established-immigrants-wealthier-than-canadian-counterparts-study-shows

Jacob, H., & Rogers, T. N. (2019, August 20). The investment firm founded by Hong Kong’s richest man, Li Ka-shing, just bought the biggest pub and brewery chain group in the UK—Here’s his incredible rags-to-riches life story. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/heres-how-li-ka-shing-became-the-richest-man-in-hong-kong-2015-6

James, C. (2012). Life at the intersection: Community, class and schooling. Fernwood Publishing.

James, C., & Chapman-Nyaho, S. (2017). ‘Would never be hired these days’: The precarious work situation of racialized and Indigenous faculty members. In F. Henry, D. Enakshi, C. James, A. Kobayashi, P. Li, H. Ramos, & M. Smith (Eds.), The Equity Myth: Racialization and Indigeneity at Canadian Universities. UBC Press.

Jefford, M. (2014) One of us or one of them: A generic qualitative study on the efficacy of the funds of knowledge strategy to reduce teacher ethnocentrism. Brock University Digital Repository. https://core.ac.uk/reader/62646570

Jefford, M. (2018). Hegemonic masculinities and intersectionality in the past and present: A theoretical feminist critique of Canada’s immigration policies for Chinese railway workers and the live-in caregiver program. In M. P. Thomas & J. House (Eds.), Symposium Proceedings: GLRC Graduate Student Symposium 2017. Global Labour Research Centre, York University. https://glrc.apps01.yorku.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/GLRC-Graduate-Symposium-Proceedings-2017.pdf

McClintock, A. (1995). Imperial leather: Race, gender and sexuality in the colonial contest. Routledge.

Pieterse, J., & Parekh, B. (1995). Shifting imaginations: Decolonization, internal decolonization, postcoloniality. In J. Pieterse & B. Parekh (Eds.), The Decolonization of imagination: Culture, knowledge and power. Zed Books Ltd.

Ponciano, J. (2020). The countries with the most billionaires. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanponciano/2020/04/08/the-countries-with-the-most-billionaires-in-2020/?sh=686ae69d4429

Rivers, O., & Ross, A. (2013). Idealized English teachers: The implicit influence of race in Japan. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 12(5), 321–339.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2013.835575

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Random House.

Slack, J. (2018, November 16). Ontario sees dramatic increase in hate crime during 2017. CityNews. https://ottawa.citynews.ca/local-news/ontario-sees-dramatic-increase-in-hate-crime-during-2017-1142305

Spivak, G. (1983). Can the subaltern speak? In B. Ashcroft, G. Griffiths, & H. Tiffin (Eds.), The Post-Colonial studies reader. Rutledge.

Spivak, G. (1995). Teaching for the times. In J. Pieterse & B. Parekh (Eds.), The decolonization of imagination: Culture, knowledge and power. Zed Books Ltd.

Stewart, A. (2014). Visitor: My life in Canada. Fernwood Publishing.

Szanton Blanc, C., Basch, L., & Glick Schiller, N. (1995). Transnationalism, nation-states, and culture. Current Anthropology, 36(4), 683–686.

Tognini, G. (2021). The countries with the most billionaires. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/giacomotognini/2021/04/06/the-countries-with-the-most-billionaires-2021/?sh=7ad3211b379b

Westoll, N. (2021). Region of Durham criticized after creating scavenger hunt for Black History Month. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/7633154/region-of-durham-black-history-month-scavenger-hunt/

Zussman, R. (2021). Horgan ‘deeply’ troubled by 717% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in Vancouver. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/7647135/horgan-bc-presser-feb-18/

Author Bio

Munjeera was an ESL Instructor and supervisor for many years. She has a Master of Education in Administration and Leadership from Brock University and is a PhD student at York University. Her research areas are inclusive strategies for learning, anti-racist curricula, and anti-oppressive immigrant education management. Munjeera loves the Raptors and Bollywood.