*For all footnotes, refer to the PDF version of the article.

Abstract

Adult ESL literacy teachers are often perplexed when instructing pre-, non-, and semi-literate adult ESL learners due to their L1 literacy level, age, and possibly traumatic experiences. Classroom instruction and assessment should be carefully planned and strategically implemented because of the underlying financial and social ties connecting literacy to socio-economic status. How might instructional practices be modified to better meet the needs of adult L2 emergent readers? This paper examines the use of Response to Intervention (RTI) tier 3 plans in adult English learning in an L2 context. For twelve weeks, several evidence-based reading diagnostics assessments were administered to help develop individualized program plans for a group of emergent readers. A comprehensive list of reading strategies and materials were used to teach letter names, grapheme-phoneme correspondence, encoding, decoding, and sight words. Participant response was examined to inform modifications to strategies and materials. Based on participant response and post-assessment gains in literacy skills, individualized program plans (IPPs) to teaching L2 literacy may be effective with adults who have limited prior formal education in their country of origin.

Background

Have you ever considered consulting K-12 reading and writing acquisition research to find possible solutions and tools to support Literacy Education and Second Language Learning for Adults (LESLLA) learners? If not, you are missing invaluable resources that can change your instructional plans and classroom teaching. To illustrate, Vinogradov (2013) encouraged LESLLA teachers to explore early literacy learning experiences in K-12 classrooms to enhance their own literacy practices. Second, Johnson (2018) found that LESLLA teachers can benefit from using a multisensory, systematic, and direct approach to reading similar to those used with L1 children with dyslexia. The researcher used Orton-Gillingham multisensory strategies and materials to teach letter names, grapheme-phoneme correspondence, encoding, decoding, and sight words to a small group of LESLLA learners for six weeks. Johnson (2018) found that modifications to strategies and materials that were developed for native English-speaking children were needed to meet LESLLA students’ learning strengths and areas of growth. Finally, Ghanem (2020) adapted Wren’s (2000) reading framework originally developed for K-12 learners to meet LESLLA learners’ needs. The researcher suggested the use of the RTI approach to introduce evidence-based intervention and assessment tools to support students who deviate from the literacy level profile of ability. She also developed a list of Diagnostic Reading Assessments (DRA) referencing K-12 literature and ATLAS, Hamline University, where numerous diagnostic tools have been developed for LESLLA teachers’ use with their students.

A new approach to address LESLLA learners’ needs

This paper represents a group of adult ESL literacy learners enrolled in CLB 3L (i.e., Canadian Language Benchmarks, level 3 in the literacy stream). Although all students have been enrolled in the same program (i.e., Foundation CLB 2L) for about two years during which they progressed through different milestones, it was noticed that they vary as far as their decoding skills and text comprehension. The first assessment tool recommended for administration is the Native Language Literacy Assessment (NLLA) (King & Bigelow, 2016) to check L1 literacy levels before embarking on other reading assessments. While NLLA results showed three students (Student M, Student A, Student F) with 0 years of education, two of those students were fluent readers/writers in their respective L1s and only one of those three students (Student F) had no literacy experience in L1.

(i) Protocol sheets choices, scoring and results: QRI-6 Word List and Reading by Analogy Test

Qualitative Reading Inverntory-6 Word List (Leslie & Caldwell, 2017) was chosen to identify the independent, instructional, and frustration levels for the learners to determine the suitable reading comprehension materials and exercises that meet the learners’ needs and adds (+1) level to the learning experiences to meet Krashen’s (1982) i+1 principle where “i” is the learner’s interlanguage and “+1” is the next stage of language acquisition. The Reading by Analogy Test (Leslie & Caldwell, 2017) was also administered to check the learners’ ability to decode by analogy.

Results for Student M: This student scored at an independent level on pre-primer 1 and 2/3, at an instructional level at premier-first grade, and at frustration level at second grade. In addition, their scores on the Reading by Analogy test ranged between 15-18. These results suggest that the learner’s decoding skills allow them to read at premier-first grade level of vocabulary. These results also suggest administering oral and silent reading of narrative and expository texts to determine the level of passages to be chosen for the next step to maintain (i+1) level of instruction.

Results for Student A: This student scored at the independent level on pre-primer 1 and 2/3 as well as at premier-first grade, at an instructional level at second grade, and at frustration level at third grade. In addition, the student’s score on Reading by Analogy Test was 14. These results suggest that the student’s decoding skills allow them to read at premier-second grade level of vocabulary, and if/when it leaps to third grade, it hits the frustration level. These results also suggest administering oral and silent reading of narrative and expository texts to determine the level of passages to be chosen for the next step to maintain (i+1) level of instruction.

Results for Student F: This student scored at an independent level on pre-primer 1 and at frustration level at premier 2/3. In addition, the student’s scores on Reading by Analogy was (9-8). These results suggest that the student’s decoding skills allow them to read at pre-premier 1 grade level of vocabulary and if/when it jumps to pre-primer 2/3 grade, it hits the frustration level. These results highlight the unique reading levels and needs for this student in comparison to the those of Students M and A.

(ii) Instructional plans

Reflecting on the holistic and analytic needs of the students is an essential step in developing instructional plans (Farrell, 2015). The protocol sheets’ results indicate that Student M’s instructional level is premier-first grade, Student A’s instructional level is second grade while Student F’s instructional level is aimed towards pre-primer 2/3 level. Instructional plans were developed to engage Student F in phonemic awareness (segmentation and isolation), learning one-syllable words, using logographic, and practising reading aloud; Student M and Student A engaged in reading appropriate level passages and using semantic mapping or KWL to relate their background knowledge to help process reading texts.

(iii) Implementation of an IPP to address LESLLA learners’ needs

The gathered data indicated that a few students needed Individualized Program Plans (IPPs). Response to Intervention (RTI) is an educational approach that focuses on providing quality instruction and intervention and using student learning in response to that instruction to make instructional and important educational decisions (Batsche et al., 2005). When RTI is used by educators to help students who are struggling with a skill or lesson, every teacher will use interventions. While data showed few students to need IPPs, for the purposes of this paper, a single case study approach (Stake, 1995) is used to illustrate the development and implementation processes:

1. What is the student’s attitude towards themselves as a reader, reading, and school before the diagnostic assessments were administered?

Student F, a pseudonym, is a 55-year-old Somali speaker. She has been enrolled in the ESL literacy program for two years during which she attended foundational literacy classes and started CLB 3L in September 2019. General classroom observation indicates that student F is a struggling reader and a dependent learner. For example, Student F refers to Somali-speaking classmates to understand classroom instructions and navigate worksheets. When Student F submits her work to be reviewed by the teacher, she often says, “please help me, reading … very hard.” While research suggested different tools to assess students’ attitudes towards reading (McKenna & Stahl, 2015, p. 240), preference was given to semi-structured interviews to accommodate the student’s reading ability of questionnaires, interests’ inventories, classroom observations, etc. The interview questions included:

- Do you like to read? Why/why not?

- Are you a good reader? Why do you think so?

- What makes someone a good reader?

- If you were going to read a book (i.e., pattern books), what would you do first?

- What do you do when you come to a word you do not know?

- What do you do when you do not understand what you have read? Maybe wait for the teacher to explain?

- Tell me about the best story or book you have ever read.

Classroom observations and anecdotal notes were taken during everyday instructional activities and intervention instruction to observe the student’s reactions and learning behaviors.

2. What are the student’s diagnostic assessment tools administered? What are the results of the administered diagnostic assessment tools? In other words, what were the major reading problems identified?

A. Native Language Literacy Assessment (NLLA) (King & Bigelow, 2016) was administered to determine the student’s reading/writing ability in Somali and Arabic since the student is a fluent speaker of both languages and lived in Somalia and Saudi Arabia for 50 years before coming to Canada. Checking and confirming L1 literacy levels, or lack thereof, before embarking on other reading assessments is an important step.

B. Using the Cognitive Model to Reading Comprehension (McKenna & Stahl, 2015, p. 8) indicates focusing on Pathway#1 which is “automatic word recognition”. Therefore, these assessment tools were administered:

Checklist for Concepts of Print (Form 4.1) and Book Handling Knowledge Guidelines (Form 4.2)

Student F had developed most of the print concepts measured by this test. When asked which page tells the story, Student F pointed to the picture. She was able to identify a word or the end of the story. Student F needed direct instruction on the concept of words and continued exposure to print.

Qualitative Reading Inventory (QRI-6): Word identification lists

The word identification section of the QRI-6 consists of word lists, with 20 words in each word list except for the pre-primer 1 which contains 17 words. The word lists begin with a pre-primer readability level and end with a junior high readability level. As a starting point, I began by administering a graded word list by using the QRI-6 tests designed for pre-primers (1-3). The reason I administered the tests of these levels was that I did not know Student F’s actual literacy level and wanted to look into word recognition ability by using several tests. I started by administering pre-primer 1 and discovered that she was reading at an independent level (17/17 = 100%). However, Student F was completely frustrated when pre-primer 2/3 was administered list (13/20 = 65%).

Qualitative Reading Inventory (QRI-6): Oral reading

The oral reading section of QRI-6 consists of both narrative and expository passages ranging in readability levels from pre-primer, primer, and first-grade passages through junior high level. Scores are derived from the number of total miscues as well as the student’s ability to answer comprehension questions. Some comprehension questions have answers that can be found directly in the text, and some have answers that require the student to infer information from the text. I administered pre-primer 1 narrative text, I Can, to assess Student F’s oral reading. Student F could partially answer the concept questions and she read it with a lot of miscues (9 miscues out of 37 words) such as the constant substitution of “me” for “him” implying that Student F was focused on making meaning of the text by checking the photo of the young boy. In addition, she could not retell the story or answer any comprehension questions and explained that she already had forgotten what the story was about.

Running record

Running records (Clay, 1993) are designed to capture what learners know and understand about the reading process. As they capture learners’ thinking, running records provide an opportunity to analyze what happened and plan appropriate instruction. I decided on administering this tool to identify the type of cues that Student F was using while reading: meaning, structural or visual cues so I could identify the instructional reading level of the materials to use while working with her since QRI-6 word lists and oral reading passage deemed at a frustration level for her. In addition, Student F read the text slowly; it took her almost 13 minutes to read 151 words. Student F attempted to break down the words and took long pauses while reading the text. The reading record sheet shows that Student F tried to use meaning and visual cues; nonetheless, she mostly used the visual ones, such as her use of “car” instead of “care” and “tired” instead of “tried”. While Student F was not able to respond to comprehension questions or retell the story, she read the book with 90% accuracy rate.

Informal phonetic inventory/survey

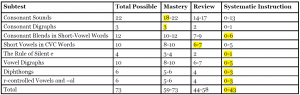

Informal phonics survey is a criterion-referenced measure to assess the student’s knowledge of letters and sounds in isolation and in words. The QRI-6 Word Analysis Test indicated that Student F knew beginning and ending sounds but had considerable difficulty with consonant blends, vowel digraphs, vowel diphthongs, and silent /e/ words. Student F knew most consonant sounds except /v/ which she pronounced as /f/. She did quite well on the consonant digraphs but found consonant blends to be challenging: “drink” for “brick”, “silk” for “slick”. Vowels seems to be an area of improvement for Student F since she could not read most short vowel words, vowel digraphs, diphthongs, r-controlled vowels. This table of results illustrates her scores highlighted in yellow:

Spelling

Student F was given a list of words to copy to complete a note and was asked to write the note by imitating the provided example. The second task was used to evaluate Student F’s level of invented spelling. According to Morris and Nelson (1992), the developmental sequence in invented spelling starts with the pre-phonemic stage (writing that does not reflect sound in words) to an early phonemic stage (using an initial constant to represent a word), to a letter-name stage (using letter names to represent sounds and often omitting vowels), and finally to a transitional stage (spelling reflects all phonemic features). Some examples of Student F are shown below:

Pre-Phonemic (na), Early Phonemic (lla), Letter-Name (No), Transitional Stage (my, bekse), Correct (sick, today)

The analysis of Student F’s spellings showed that most of her words ranged between early phonemic and correct spelling. Her writing commonly featured the use of consonants to represent initial sounds; sometimes final sounds were represented too, but the spellings were incomplete. Her writing showed her discovery that letters in print represent sound in spoken words and indicated the beginning of the ability to segment phonemes.

In summary, based on the six diagnostic reading measures explained above, Student F’s test scores fell within a range of limited proficiency with reading in English. Student F’s comprehension and word recognition were found to be at a frustration level when she was tested using primer 2/3 assessment tools. Therefore, the student was placed at an instructional reading level in both word recognition and was introduced to pre-primer 2 reading materials for instruction as well as given more difficult materials as she progresses.

(3) What are the recommended reading intervention strategies to enhance student’s literacy growth?

There are a few strategies that are recommended for Student F in addition to the core classroom instruction as per the Minnesota Reading Association and Department of Education recommendations (2011):

A. Interest and self concept:

Developing a positive orientation toward reading about a relevant topic is expected to motivate Student F to build her reading stamina and her self-perception as a reader. This included conducting classroom observations during which information about student F’s likes and dislikes were collected, interest inventories which are a list of topics used to identify the ones individual students find appealing. As it has been noted that Student F’s main reading challenges are due to her beginner decoding skills, as she often says “reading … very hard”, two strategies were used to improve her self concept as a reader: 1) Reading aloud to Student F to relieve her from the cognitive load of decoding while acquainting herself with books of her interest; 2) Developing and using materials of appropriate difficulty level, whether printed or digital:

- Printed books, such as Photostories, which places limited demands on her beginner decoding skills;

- Digital books that provide Canadian relevant content, Story Books Canada (choose Canada from the menu on the left of the page);

- Digital books that provide L1 support to facilitate meaning and enhance self-concept

B. Phonemic awareness (PA):

Phonemic awareness and word analysis help learners become familiar with how the English language writing system works—an essential step in learning to read. Students with good phonemic awareness know how to manipulate the individual sounds (i.e., phonemes) of spoken English. To illustrate, Student F knew that the spoken word car is made up of three sounds: /c/-/a/-/r/ and could distinguish each sound based on place and manner of articulation. The National Reading Panel (NRP, 2000) summarizes phonemic awareness tasks: phoneme identity, isolation, categorization, blending, segmentation, and deletion (pp. 2–10). Two digital resources were used to enhance PA to introduce English phonemes in terms of description and place, and manner of articulation, e.g., University of Iowa’s Sound of Speech and IXL to practice. In addition, Reading Rockets was used for working with phonics instruction, oddity tasks, stretch sounding, invented spelling, tongue twisters, adding sounds, deletion tasks, and onset rhymes practice.

C. Vocabulary expansion:

Teaching vocabulary is very important to comprehend meaning conveyed in the text. Teaching vocabulary can be done via explicit instruction, such as prefixes and suffixes; implicit instruction through the exposure of new reading materials to practice learning the meaning of new words; multimedia methods by going beyond the text experience, e.g., semantic mapping, where visual representations are used to illustrate the relationships among new and known word meanings; capacity methods, by allowing students to practice extensively to increase their vocabulary capacity through making reading automatic; and association methods where students learn to draw connections between what they do know and words they encounter that they do not know; “happy” and “glad” are examples. Repetition, multiple contexts, and active engagement take place routinely. In addition, Student F read word by word rather than in phrases/chunks. She also faced a few challenges with word meanings, and a lack of vocabulary knowledge caused comprehension questions to be missed. Hence, sight words were practiced to enhance Student F’s vocabulary while using the Reading Rockets website for these strategies: Concept Sort, List-Group-Label, Semantic Feature Analysis, and Semantic Gradients.

D. Fluency:

Reading fluency is not “fast reading”, but it is a “reasonably accurate reading, at an appropriate rate, with suitable expression, that leads to accurate and deep comprehension and motivation to read” (International Literacy Association, 2018, p. 2). Reading fluency is based on accuracy (reasonably accurate that is not below 95%), rate (appropriate rate level is at 50th percentile), and expression (a suitable expression that includes pitch, tone, volume, emphasis, rhythm in speech or oral reading, and the skillful reader’s ability to chunk words together into appropriate phrases). Possible ways to assess reading fluency are what Jones et al. (2010) call Qualitative Fluency Assessment (p. 47) after 60 seconds of read-aloud or using Google’s Fluent Reader App which records students reading of a text after it is analyzed in class. Jones et al. (2010) recommend that “nonfluent” and “struggling” readers “don’t offer insight the way a more elaborated description of a students’ oral reading might” (p. 46) thus making running records more informative, which was administered in Student F’s case. At this point, focusing on improving Student F’s fluency took the form of combining phonemic awareness, phonics instruction, and vocabulary so Student F could start focusing on the meaning of what she read. The following strategies via Reading Rockets were used as well: Partner Reading, Choral Reading, and Shared Reading.

E. Reading comprehension (RC):

Comprehension refers to a learner’s understanding of what they are reading. Strategies to enhance RC can be timed-based on the progression of the task:

Before-reading strategies allow students to activate and build prior knowledge as modeled by the teacher, set a reading purpose by examining text title, preview text by using pictures, analyse text structure, ask general questions to enhance predictions about the text, and develop a plan for reading the text. During-reading strategies promote active thinking to make meaning from text, maintain engagement and monitor comprehension, make connections between parts of the text, and support the purpose for reading while critically thinking about it. After-reading strategies require students to check for understanding of the main idea of the text, re-tell the sequence of events, integrate new information and prior knowledge, identify the author’s argument, answer literal and inference meaning of the text, synthesize new information and transfer learning. Sample texts are at sentence level to enhance sentence meaning and structure as well as female characters that Student F could identify with:

- Baker, J. (2010). Mirror. Candlewick Press. www.candlewick.com

- Bogart, J. E., Fernandez, L., & Jacobson, R. (1997). Jeremiah learns to read. Scholastic Canada Ltd. http://www.scholastic.ca/books/view/jeremiah-learns-to-read

- Helgerson, M. (2006). Hanatu, a seamstress, learns to read: Literacy changed my life. Osu Library Fund. www.osuchildrenslibraryfund.ca

- Kita-Bradley, L. (2012). The map: Human series. Grass Roots Press. https://grassrootsbooks.net/products/the-map?_pos=1&_sid=0f8d2f3a4&_ss=r

iv) Results and conclusion

The proposed IPP was implemented for 12 weeks and led to improving Student F’s reading level to be instructional pre-primer 2/3 when administering QRI-6 word lists and instructional pre-primer 1 when administering QRI-6 oral reading passages. The improvement in Student F’s reading level from frustration to instructional level is a testimony to the student’s hard work and the careful planning of individualised instruction. The International Literacy Association (ILA) has recommended that for students to acquire these fundamental reading skills by the end of the third grade, they need: 1) training in phonemic awareness, phonics, reading accuracy, and fluency; and 2) teachers/reading specialists/literacy coaches must familiarize themselves with state-of-the-art research, such as turning around the focus from skill training to the student themselves to identifying each student’s reader identity, fluency, and comprehension levels, hence developing reading plans to guide the teacher while supporting the student (2018). While Student F acquired the essential literacy skills in a LESLLA class where innovative teaching and learning strategies were implemented and proved successful in improving her reading level, her literacy journey resembles that of third graders because, as Vinogradov (2014) argues, “perhaps adult learning theory and how children learn are not so different after all” (p. 163) since humans want to understand the world, develop control over their lives, and become self-directed learners.

References

Batsche, G., Elliott, J., Graden, J. L., Grimes, J., Kovaleski, J. F., Prasse, D., Schrag, J., & Tilly, W. D. (2005). Response to intervention: Policy considerations and implementation. National Association of State Directors of Special Education, Inc.

Clay, M. (1993). Reading recovery: A guidebook for teachers in training. Heinemann.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2015). Promoting teacher reflection in second language education: A framework for TESOL professionals. Routledge.

Ghanem, E. (2020). A framework and curriculum for teachers of adult English language literacy learners: Incorporating essential skills and intervention plans for ALL/LESLLA learners. School of Education Student Capstone Projects, https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_cp/502/

International Literacy Association. (2018). Explaining phonics instruction: An educator’s guide. International Literacy Association. https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/where-we-stand/ila-explaining-phonics-instruction-an-educators-guide.pdf

Johnson, S. (2018). Modifying Orton-Gillingham multisensory strategies and materials for a LESLLA learner context. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy,

http://hdl.handle.net/11299/212928

Jones, S., Clarke, L., & Enriquez, G. (2010). The reading turn-around: A five-part framework for differentiated instruction. Teachers College Press.

King, K. A., & Bigelow, M. (2016). Native language literacy assessment. University of Minnesota, CEHD. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B64uvB4u-xaVaFh2QXhzLXUxSzQ/view

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon.

Leslie, L., & Caldwell, J. A. (2017). Qualitative reading inventory: 6. Pearson.

Minnesota Reading Association (2011). An updated model plan for adolescent reading intervention and development. Minnesota Reading Association. http://mra.onefireplace.org/page-1222634

McKenna, M. C., & Stahl, K. A. D. (2015). Assessment for reading instruction (3rd ed). Guilford Press.

Morris, D., & Nelson, L. (1992). Supported oral reading with low achieving second graders. Reading Research and Instruction, 32, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388079209558105

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction.

https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

Vinogradov, P. (2013). Professional learning across contexts for LESLLA teachers: The unlikely meeting of adult educators in kindergarten to explore early literacy Instruction. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Minnesota]. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/148908/Vinogradov_umn_0130E_3523.pdf;jsessionid=366DC0EADDA4BAEDDA64E6C12DC56E0B?sequence=1

Vinogradov, P. (2014). Adult ESL and kindergarten: An unlikely meeting to improve literacy instruction. MinneTESOL Journal, Spring 2014. https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/176676

Wren, S., & Educational Resources Information Center (U.S.). (2000). The cognitive foundations of learning to read: A framework. Southwest Educational Development.

https://sedl.org/reading/framework/framework.pdf

Author Bio

Eman Ghanem, MEd, MA, MALEd, has been working in the ESL field as a teacher, assessor, researcher, literacy coach, reading specialist, and lead instructor. She enjoys supporting CLB and Foundations Literacy Programs in Edmonton. Since 2012, Eman has been working for the Edmonton Catholic Separate School District (ECSD) LINC programs where she helps adult ESL literacy students tackle the intricacies of language learning and collaborates with teachers to thrive in F2F and online classrooms.