A review of the framework and its writing continua

Abstract

Given the current increased presence of English Language Learners (ELLs) in our Ontario elementary and secondary classrooms, teachers are faced with a challenging task of assessing each student’s language ability, placing students in suitable programs, and tracking progress. The Steps To English Proficiency is a tool developed by the Ministry of Education, team of educators, and experts in assessment and content that will support classroom teachers to make appropriate decisions and continue to track their students’ performance in order to make the most suitable choices for their students. This article will specifically review the writing portion of the framework and hopes to provide insight to teachers who may be interested to adopt this framework by highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of this framework.

Ontario’s elementary and secondary classrooms have been quickly evolving as their student populations have become increasingly diverse. To properly address the particular needs of each student, classroom teachers need the best knowledge and tools to properly assess and track each student’s progress. The Steps To English Proficiency assessment framework (STEP) is a tool designed for teachers to evaluate their students’ language development across oral language and literacy (reading & writing) skills and offer in-depth insights into best assessment practices and teacher development in the classroom setting. To our knowledge, there have been no objective reviews of this unique assessment framework. Therefore, this paper will provide an overview of the history, content, and educational purposes of STEP in relation to the contextual needs of teachers in the classroom. As we believe that writing is a critical skill that can propel students toward better academic success, this review will place a specific focus on the writing portion of the STEP, looking at the continua in all four-grade clusters (Grades 1–3, 4–6, 7–8, and 9–12).

History

In Ontario, elementary and secondary classrooms are largely composed of students whose first language is not English. These students are referred to as English Language Learners (ELLs). These students can be new immigrants or students born in Canada and living in multilingual environments (Jang, 2014). The initiative to address the language needs of the growing population of ELLs began in 2005 from a response to an Auditor General for Ontario’s report (Office of the Auditor General of Ontario, 2005) regarding the status of English as a second language (ESL) and English as literacy development (ELD) in Ontario classrooms (Jang, Wagner, & Stille, 2010). The Auditor General report noted that there was a lack of information regarding how ELLs’ English language ability improved and suggested the need for a tracking tool to understand both where the allocated funding was distributed and how ESL and ESD programs were implemented. To address the concerns in the report, from 2008 to 2011 the STEP proficiency scales were developed, validated, and field-tested with various stakeholders such as teachers, assessment experts, and ESL specialists (Jang, Wagner, & Stille, 2011). Following this, the STEP framework was introduced in 2012 and integrated within various school boards across Ontario.

The main purpose of the STEP assessment framework was to address the increasing achievement gap of ELLs with a focus on the classroom context, targeting both oral language and literacy skills (reading and writing). Results from the 2012 Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test (OSSLT) alarmingly identified that while 82% of first-time eligible students passed the test, only 66% of the ELL population did so (Zhang, Shulman, & Kozlow, 2014), suggesting a critical demand for support. Thus, an assessment framework like STEP is a useful tool, and the first in Ontario that allows teachers to track ELLs’ language trajectory. To do so, STEP is constructed with more skills-based descriptions of student abilities and competencies. It is a descriptor-based proficiency scale, a current, global, assessment trend (Stille, Jang, & Wagner, In press). Unlike other descriptor-based proficiency assessments (e.g. Canadian Language Benchmarks (CLB), the American Council of the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), and World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) English Language Proficiency), STEP is embedded in the Ontario curriculum and is specifically used for classroom-based assessment (Stille, Jang, & Wagner, In press).

Defining Writing

Any valid assessment measure must be grounded within a theoretically and empirically sound definition of the thing that is being assessed (i.e. a construct definition). Within the STEP framework, writing is seen as a process (rather than a mere product) that moves from “pre-writing and organization of ideas, to writing and editing” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2012, p. 13). Jang, Wagner, & Stille (2011) note that this view of writing is supported by theories from Seow (2002) and Tribble (1996). It is important to note here that the content for the entire STEP framework was negotiated amongst three major groups of stakeholders: teachers in Ontario, the Ontario Ministry of Education, and a team of external researchers and content experts. The specific language chosen for all of the Observable Language Behaviour (OLB) continua (both descriptors and elements) resulted from these negotiations. For example, the wording of the STEP descriptors is linked to curriculum standards.

Continua Content

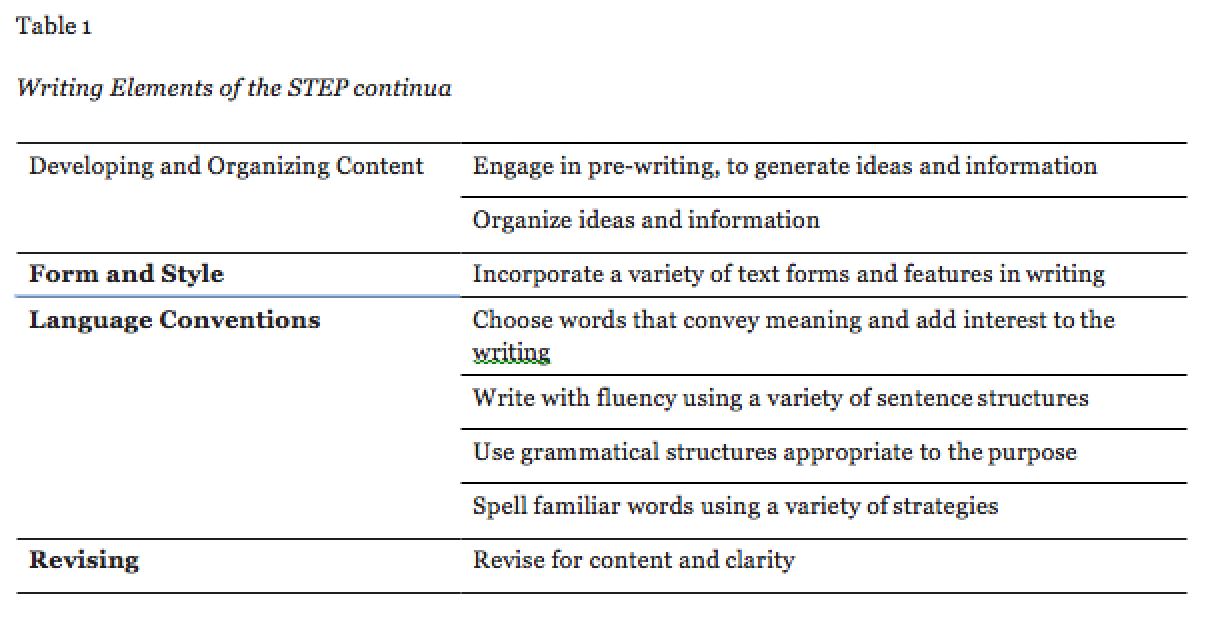

The STEP OLB writing continua consist of OLBs, particular language behaviours that are strongly tied to curriculum standards and can be observed in students’ daily classroom activities across all subjects. The OLB writing continua for each grade cluster is composed of four “Elements”’ (i.e. dimensions) and six “Steps”. The elements and their sub-dimensions are listed in Table 1.

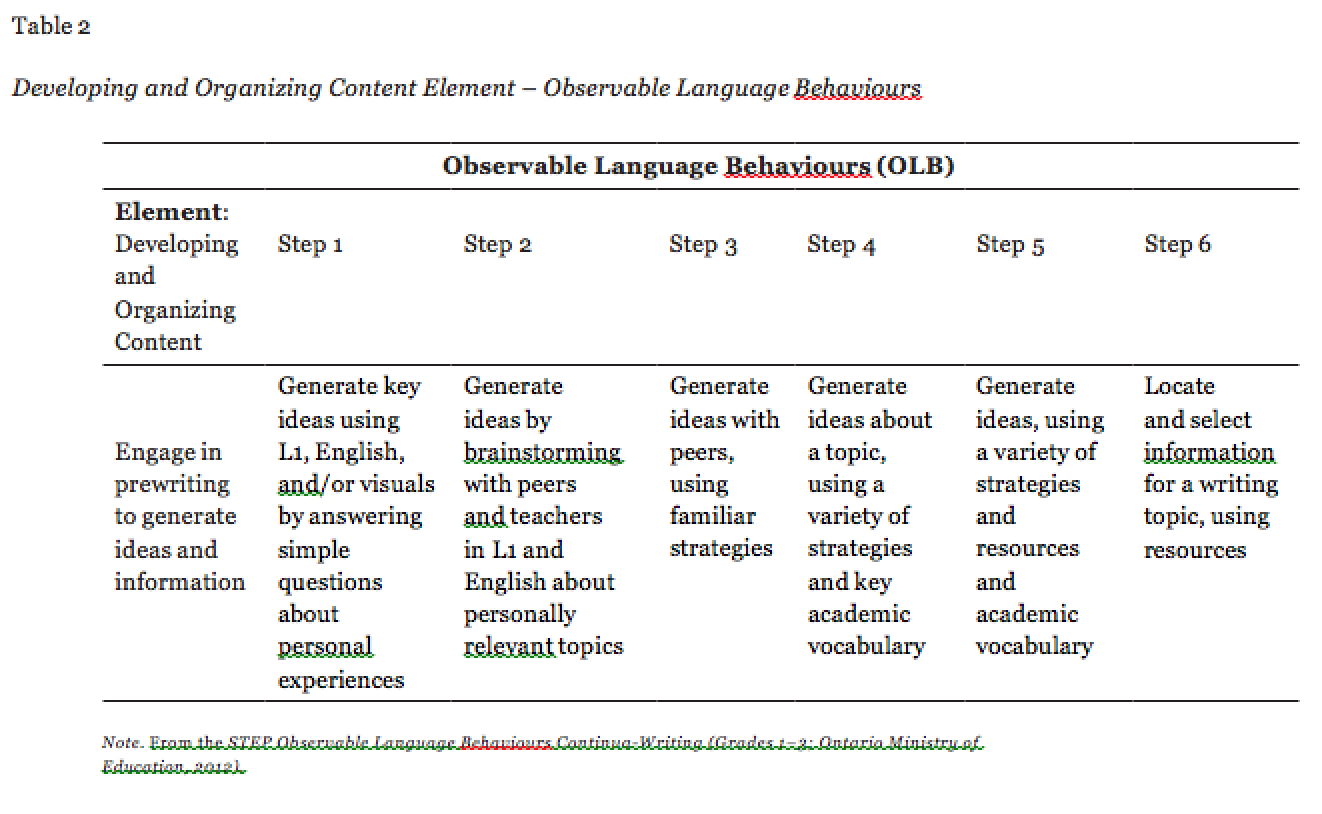

Each OLB writing continuum consists of positively worded descriptors, which highlight students’ abilities, rather than their deficiencies. Table 2 contains the descriptors for steps 1–6 for the grade 1–3 cluster in one section of the Developing and Organizing Content element and serves to further illustrate this point.

The descriptors for each grade cluster are tied to curriculum demands and teacher expectations and are, as such, quite distinct from each other. Recent research by Jang, Cummins, Wagner, Stille, and Dunlop (2015) provides empirical evidence of how distinct the descriptor definitions are across the three modalities (speaking, reading, and writing), as well as how similar these descriptors are within proficiency levels. It is essential to empirically confirm that descriptors are distinct from each other to ensure that each step sequentially builds upon the previous step in order to track student progress. In other words, if the steps are too similar, then it may become unclear what a “1” means versus a “2”, and the steps will lose their meaning.

However, there are differences regarding the students’ use of their first language (L1) across age clusters. All of the OLBs for writing anticipate students to use their L1 in Steps 1 and 2, but there are differences among the Elements in which L1 use is expected. In the 1–3 cluster, L1 use is expected in 3 of the 4 Elements (except Revising), while in the 4–6 and 7–8 grade clusters, L1 use is expected only in the Developing and Organizing and Form and Style Elements. In the 9–12 grade cluster, use of L1 is only anticipated in the Developing and Organizing Element. The different treatment of students’ use of their L1 in different grade cluster indicates a potential disadvantage for older ELLs. While the curriculum expectations are certainly more cognitively challenging as grade level increases, it is not clear why students’ limited use of their L1 could not be accepted in the same elements in steps 1 and 2 across age clusters. Denying students’ initial use of their L1 as they develop their English skills may have detrimental effects and prevent students from achieving their full potential. Thus, it would be valuable to add descriptors that include the use of the L1 in steps 1 and 2 in three of the four elements (of the writing continua).

Implementation

The continua are frameworks and are therefore meant to be used on a continual basis to inform lesson plans and other pedagogical decisions, as well as other assessments of students’ work and classroom behaviours. They are to be used by all classroom teachers, regardless of discipline, as well as ESL/ELD teachers to assess and track the language development of ELLs. The STEP Users Guide (2012) suggests using the OLBs for tracking purposes at least once a year. It can be assumed that students will progress differently in different elements. For example, it would be possible for a student to be at step 2 for Revising, but at step 3 for Developing and Organizing. However, students can only progress to a “higher” step if teachers have observed all OLBs in all four elements of the current step. Regarding the example above, tracking records would only indicate that student had overall completed step 2. Practical implementation of the STEP would be limited when teachers have dividing opinions of whether a student has achieved all Elements of a Step or not. This poses difficulty in the tracking procedures of STEP and teachers need to be more aware of their own interpretations of the step descriptors.

Limitations and Suggestions

Each teacher offers their own unique perspectives of their students and as such there should be measures in place to ensure accountability regarding teacher use and interpretation of the continua. There are currently no such measures in place and this calls the reliability (particularly inter-rater reliability) of the continua into question. One way to ensure a reliable use of the continua would be to have teachers from different disciplines and grades share perspectives on each student’s language development with each other. This would have the added benefit of strengthening teachers’ own classroom activities and assessment tasks.

While the STEP framework is flexible in its application and interpretation, it is quite inflexible regarding the process (for tracking purposes) through which a student can be said to have completed a particular step. A student must demonstrate all aspects of the four elements in order to complete that step. It could be argued that this is a rather narrow view of language development that focuses more on what students still cannot do (i.e. their deficiencies), rather than what they can do (i.e. their abilities). If a student has mastered one of the elements in a step, that should be acknowledged and they should be given more challenging tasks informed by the descriptors in the next step. It may be more useful, then, to have each element and its accompanied step in its own continua. This would provide a clearer picture of students’ language development for whomever is reading the student’s tracking record.

Strengths and Suggestions

A major strength of the STEP is that the descriptors have been developed through discussion with various experts such as teachers, education professionals, and assessment experts. While different stakeholders’ perceptions of each construct can lead to validity concerns, it could be argued that these descriptors are better representations of the construct definitions most relevant to classroom-based assessments. Through the validation studies, teachers’ inputs were crucial to appropriate the language used in the descriptors. Given that teachers are the primary users of STEP, the assessment framework utilizes descriptors that are applicable to teachers’ classroom context so the framework can be broadly interpretable.

Another strength of STEP is its flexibility as a framework meant merely to guide teachers. But, this flexibility could also be seen as a burden for some teachers who may not have received education or training on how to prepare a range of materials that target specific descriptors of each element. In order for STEP to be easily accessible and pertinent to teachers’ preparation of materials, the STEP User Manual (2012) should include examples of activities and assessment tasks that would elicit the skills in each element. This suggestion is not meant to restrict or direct teachers’ work but rather is intended to support and optimize teachers’ preparation.

Moving forward from the validation studies and field-testing, framework developers and experts should follow-up with teachers who are currently utilizing STEP in their classrooms. Factors such as the practicality and applicability of the framework in the classroom context should be further investigated. Also considering other contexts, we would recommend other educational systems consider using a framework such as STEP for their own classrooms. It is important to note that STEP is highly context-specific, so its applicability to other contexts should stem more from its theoretical perspective on language development rather than its particular descriptors, elements, or continua. Supporting ELLs’ language development in any school should not only concern language, ESL, or English teachers, but teachers in all subjects and classroom contexts. The more teachers understand the unique needs of each student, the better they can provide essential supports and activities to create a truly equitable learning environment for all students.

References

Jang, E. E. (2014). Assessing English language learners in K-12 schools. Education Matters, 2(1), 72–80.

Jang, E. E., Cummins, J., Wagner, M., Stille, S., & Dunlop, M. (2015). Investigating the homogeneity and distinguishability of STEP proficiency descriptors in assessing English Language Learners in Ontario schools. Language Assessment Quarterly, 12, 87–109.

Jang, E. E., Wagner, M., & Stille, S. (2010). A democratic evaluation approach to validating a new English language learner assessment system: The case of Steps to English Proficiency. English Language Assessment, 4, 35–50.

Jang, E. E., Wagner, M., & Stille, S. (2011). Issues and challenges in using English proficiency descriptor scales for assessing school-aged English language learners. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 45, 8–14.

Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. (2005). 2005 annual report of the office of the auditor general of Ontario. 9–10. Retrieved from http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/reports_en/en05/en_2005%20AR.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2012). STEP: Steps to English proficiency: A guide for users.

Ontario: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.edugains.ca/resourcesELL/Assessment/STEP/STEPUserGuide_January2012.pdf

Seow, A. (2002). The writing process and process writing. In J. C. Richards and W. A. Renandya (Eds), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 315–320). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stille, S., Jang, E., & Wagner, M. (In press). Building teachers’ assessment capacity for supporting English Language Learners through the implementation of the STEP language assessment in Ontario K-12 schools. TESL.

Tribble, C. (1996). Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zhang, S., Shulman, R. & Kozlow, M. (2014). Tracking student achievement in literacy over time in English-language schools: Grade 3 (2005) to grade 6 (2008) to OSSLT (2012) cohort. (EQAO Research: Research Report).

Author Bios

Elizabeth Jean Larson ( jeannie.larson@mail.utoronto.ca ) has taught ESL for 10 years in Japan, Germany, and Canada. She has taught students of all ages in contexts varying from private junior and senior high schools, to private conversation schools, to business courses conducted in-company. She completed her Masters in Education in the Language and Literacies Program at OISE in the spring of 2016 and began her PhD in the same program at OISE that following September. Her research focuses on language education and language assessment, particularly regarding oral language.

Clarissa Lau is a third year doctoral student in the Developmental Psychology and Education program at OISE. Her teaching experiences have included high school and adult ESL learners as well as individuals with special needs. She has also developed curriculum materials for high school and adult ESL learners. Her main research interests involve issues of emotional regulation, assessment, and language development. She is involved in various research initiatives investigating cognitive, metacognitive, and affective factors that influence literacy development. She is currently involved in a provincial initiative to develop a language framework to assess and track oral language in the kindergarten years.